Pyramids

There is a stereotype that the Egyptian pyramids are located somewhere far away in the middle of a barren desert, and it takes half a day to get there without stops. Most likely, this myth arose from tourists who take a bus tour to the pyramids and travel halfway across Egypt from some place like Hurghada.

In reality, the pyramids are literally within the city limits of Cairo, specifically its western part called Giza. They can be clearly seen right from the rooftops of residential buildings.

Every morning during his stay in Giza, the author would wake up and first approach the curtains covering the terrace with a view of the pyramids. Asking himself, “Still there?” he would immediately pull back the curtains and answer himself, “Still the-e-ere.”

The pyramids have successfully been there for 4,600 years and will likely be there for that many more. Perhaps the pyramid shape is so simple and stable that even ISIS are powerless: it’s not even possible to blow them up. Especially since the entrance to them is guarded by the Sphinx.

Well, since they will be there for that long, we have plenty of time. Therefore, before exploring the pyramids of Giza, let’s move 25 kilometers south of Cairo to a place called Saqqara — the oldest cemetery on the outskirts of the city of Memphis, the former capital of Ancient Egypt.

Djoser’s Mastaba

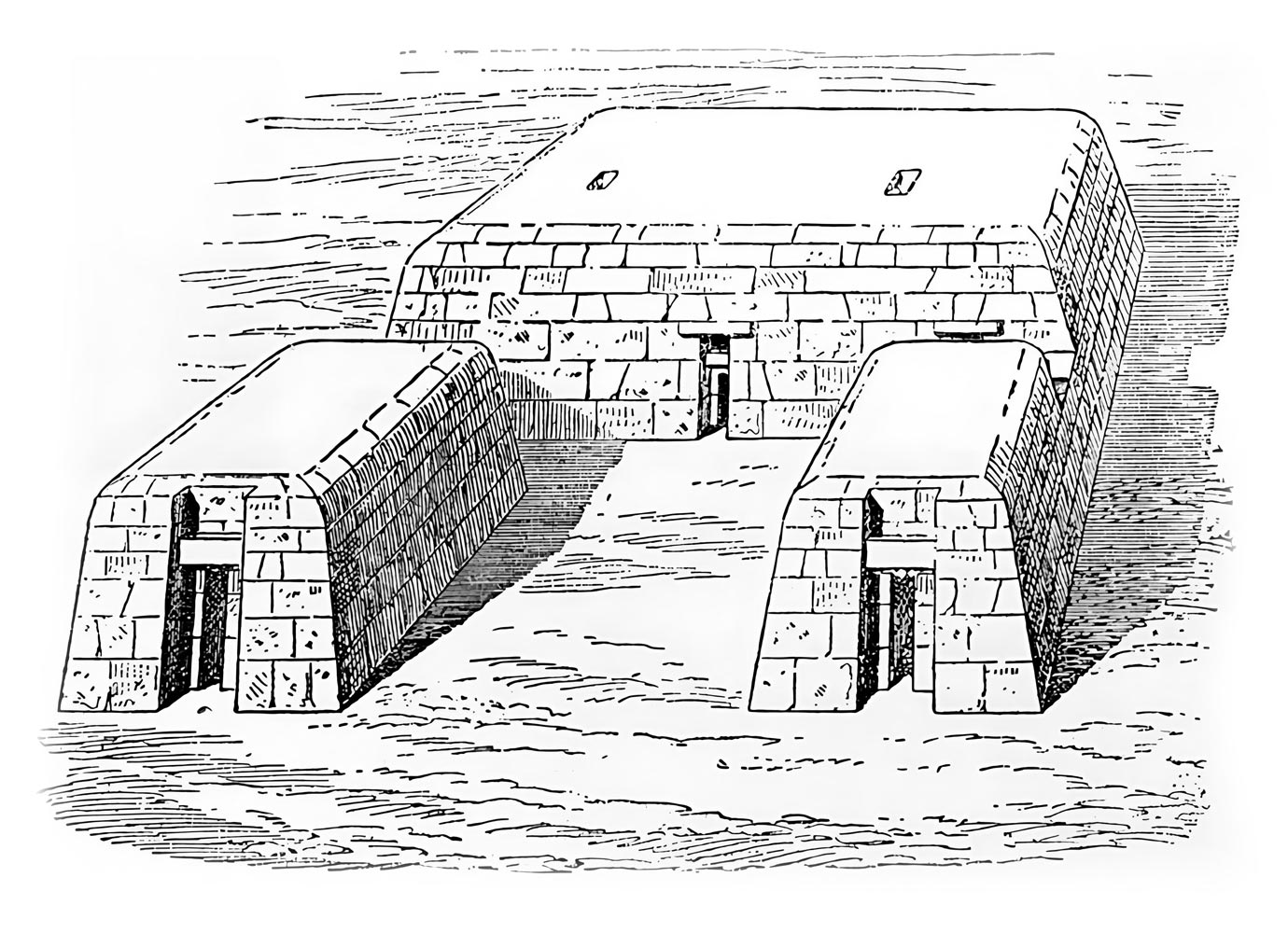

Egyptians came up with the idea of arranging lavish funerals for their rulers with burial in gigantic tombs long before the invention of pyramids. It was customary to bury pharaohs of the first dynasties deep underground, with a large rectangular tombstone constructed above the grave. Initially, these tombstones were made from mudbrick, and later they began to be built from stone.

Such tombstones had an entrance leading to a small room that served as a chapel for conducting memorial rituals by the deceased’s family members. From the tombstone, one could also access a shaft that led underground to the burial chamber, where the body of the deceased was kept. This chamber was usually lavishly decorated and furnished with treasures, so it was carefully sealed and concealed.

Such tombstones were called by the ancient Egyptians per-djed, or “house of eternity.” Today they are known by the Arabic word “mastaba,” which translates to simply “bench.”

Although mastabas were an Egyptian invention, they were not entirely unique. Similar structures existed at the same time in Mesopotamia and were called ziggurats.

All pharaohs would have continued to be buried in brick ziggurats if around 2667 BCE in Egypt had not appeared Imhotep — the first scientist in history whose name has come down to us.

Imhotep probably meant even more to the Egyptians than Socrates did to the ancient Greeks. He was a philosopher, astrologer, physician, and architect. Imhotep’s authority was so incredible that he eventually came to be regarded as the god of medicine and the patron of scribes. He was credited with magical abilities and the gift of healing, and he was also credited with saving Egypt from drought: Imhotep thought to create grain reserves.

As the court architect for a pharaoh named Djoser, Imhotep oversaw the construction of his mastaba. In an effort to demonstrate the power of the new Egyptian dynasty, Djoser tasked Imhotep with building the largest mastaba in existence. And he built a mastaba in the Saqqara necropolis measuring 63 meters on each side and about 7.5 meters high. It seems that this was the first truly large stone structure in the entire world.

However, Djoser was not satisfied. So Imhotep soon extended the original mastaba almost double: to 120 meters on one side and 105 meters on the other. This still wasn’t enough, so Imhotep decided to develop the structure vertically and built another slightly smaller mastaba on top of the first. Then he built a third and a fourth on top of the second — continuing this way until there were six mastabas stacked on top of each other, reaching a height of 60 meters.

The step ziggurat constructed by Imhotep went down in history as Djoser’s mastaba. It became the first Egyptian pyramid.

The purpose of the steps was purely symbolic. It was most likely intended that the deceased pharaoh would ascend to the heavens via these steps. Besides the steps, Djoser’s mastaba differed from all previous mastabas in that for the first time it was built from stone, rather than mudbrick. In result, it is the oldest stone structure in the world, and it has survived in remarkably good condition for a building that is 4,600 years old.

The Bent Pyramid

Djoser’s step pyramid is the only one of its kind that has survived to this day. The rulers of the next dynasty had the idea that a pyramid would be much more elegant if they could eliminate the steps and make it smoothly taper upward.

Pharaoh Sneferu was the first to order the construction of such a pyramid. His first pyramid has not survived to this day, but it is known that it was initially constructed following Djoser’s pyramid’s principle, and then the gaps between the steps were filled with limestone. Sneferu’s second pyramid has survived and does not use levels at all; it tapers smoothly upward without any filling.

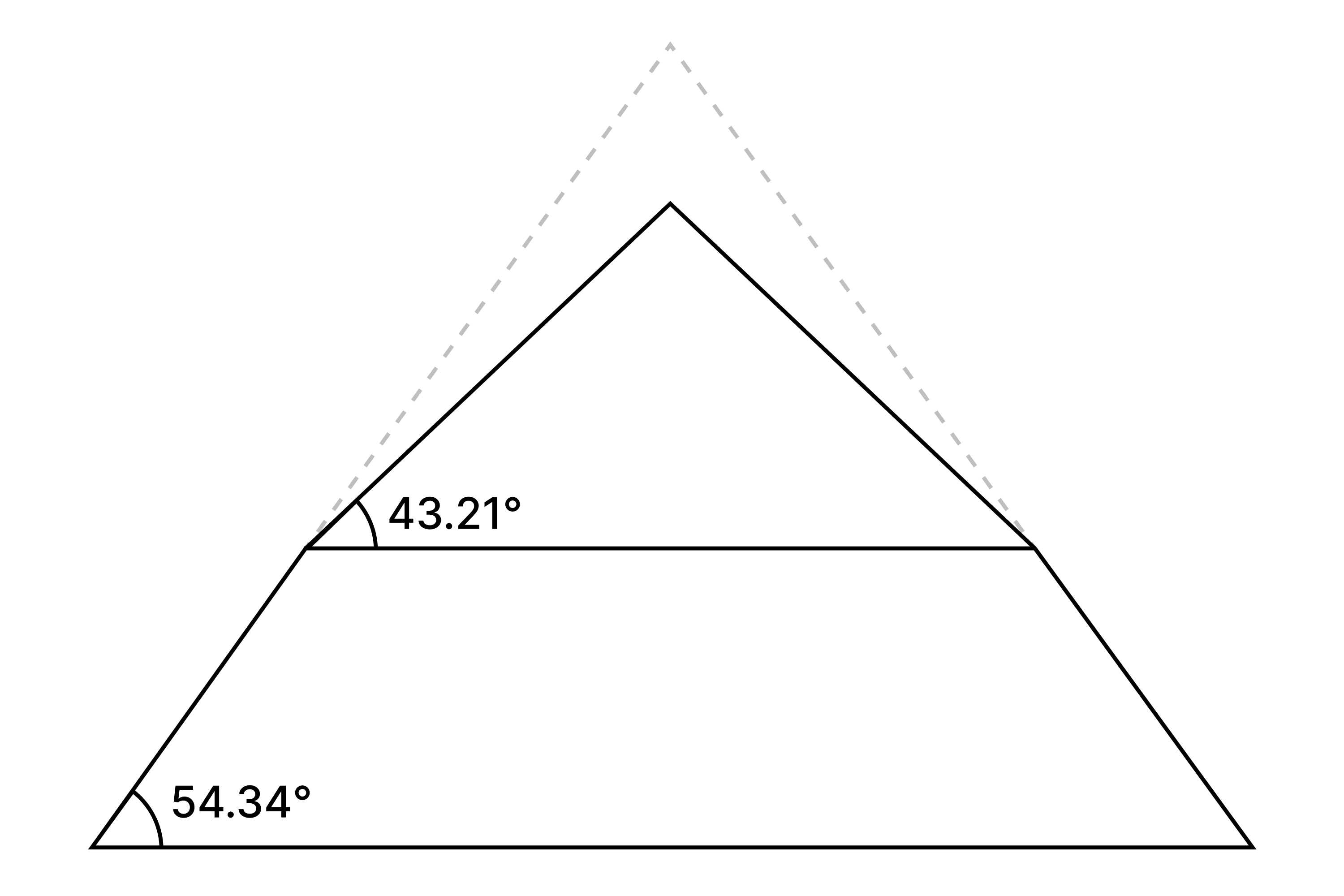

However, the walls of this pyramid taper unevenly. The angle of the walls at the base is 54 degrees, decreases to 43 degrees toward the top.

There are several theories about why the pyramid ended up this way. The most convincing one suggests that Sneferu unexpectedly died during its construction. To finish it more quickly and bury the pharaoh, the builders sharply changed the angle of inclination, making the pyramid significantly shorter.

Regardless of the reason, Sneferu’s pyramid went down in history as the Bent Pyramid.

Up close, it is visible that the Bent Pyramid is constructed from rather large stones. Over time, it has started to crumble, so supports have been installed in some places.

Despite this “restoration,” the Bent Pyramid, built in 2596 BCE, is in significantly better condition than the nearby Black Pyramid, which was constructed 700 years later. The reason is that the Bent Pyramid was built from stone, while the Black Pyramid was constructed using the old method with mudbrick. It is visible from the top of the Bent Pyramid: after many centuries, almost nothing remains of it.

You can descend into the Bent Pyramid. The entrance is located in the middle of the pyramid, several meters above the ground.

It is a narrow tunnel that leads downward at a steep angle. Such tunnels in pyramids are called shafts.

The shaft barely accommodates one person. The floor has wooden planking, and railings are attached to the walls; without them, it would be nearly impossible to climb back up.

The Bent Pyramid is quite interesting inside. Unlike other pyramids, whose shafts lead to a small room with a sarcophagus, the shaft of the Bent Pyramid leads to a rather spacious underground chamber shaped also like a pyramid. From this chamber, another tunnel goes upward, leading to a second chamber, similar to the first but 12 meters above the ground.

The biggest problem when inside the pyramid is the incredibly dry air. It feels as though not even a draft has penetrated here in four thousand years.

I think it’s quite possible to faint here. Imagine that you’ve just crawled down a long shaft on all fours and then climbed up a steep ladder. You are breathing heavily, but the pyramid air seems to have little oxygen. As a result, your vision darkens, and your head spins.

The second chamber turned out to be quite spacious, more like a cave.

Bats were found on the ceiling. How did they even get in here, and what do they eat? Do they really crawl through this entire shaft system every night and then climb back in? No, there must be crevices somewhere in the walls of the pyramid.

The Pyramid of Khufu

Now it’s time to return to Giza.

Sneferu’s successor was his son, Khufu. With Sneferu’s death, the era of bent pyramids ended. Starting with Khufu, all pyramids became geometrically perfect, and the scale of construction reached its peak.

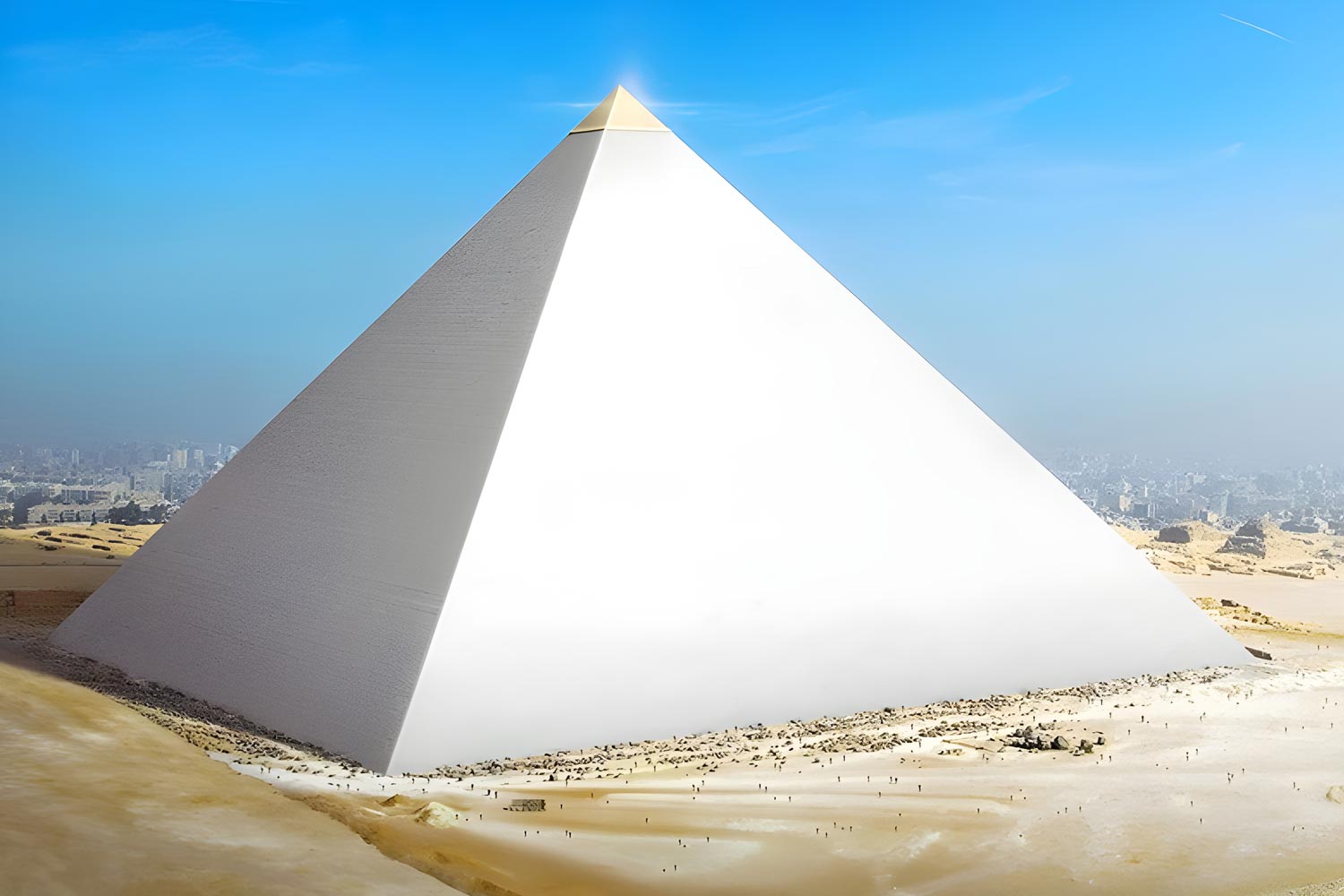

To definitively settle the matter of greatness, Pharaoh Khufu decided to build a truly gigantic pyramid. It was completed around 2580 BCE, just 100 years after Imhotep built Djoser’s mastaba.

Unlike his predecessors, Khufu decided to build the pyramid not in Saqqara but 25 kilometers to the north — where Giza and Cairo are located today. It was an ideal new site for a truly great pyramid: a large, rocky plateau on elevated ground near a major quarry.

Khufu’s pyramid was constructed from two million three hundred thousand stone blocks, each weighing 2.5 tons. The pyramid reached a height of 146 meters, and the length of each side of the base was nearly a quarter of a kilometer! Unfortunately, we do not know how many people were involved in building this pyramid, as no records have survived. The ancient Greek scholar Herodotus wrote of 100,000 workers, while modern scholars estimate only 20,000 to 30,000 people.

Khufu’s pyramid has remained the largest pyramid in the world. No one has ever surpassed this giant.

Today, Khufu’s pyramid is the main attraction in Egypt, drawing tens of thousands of tourists to Giza.

The reader may have already guessed that I’m writing with a twist. After all, in the photographs, it’s the Pyramid of Cheops. Exactly!

When Herodotus arrived in Egypt and overestimated the number of pyramid builders by five times, he also misread the Egyptian hieroglyphs, which had long been out of use by then. As a result, he wrote the pharaoh Khufu’s name in Greek as Cheops. This is the name by which he and his pyramid entered history.

You can descend into the Pyramid of Cheops, and there is a significant line at the entrance.

The author implores the reader against this ill-considered action. There is absolutely nothing to see inside the Pyramid of Cheops. Descending into the tomb is incredibly difficult and time-consuming, and the entrance fee is nearly 30 dollars. Everyone emerging from the shaft says the same thing: it’s not worth it. It’s better to visit Saqqara and explore the Bent Pyramid instead.

Despite Cheops’ absolute record, his successors attempted for some time to surpass the Great Pyramid. However, building something more colossal proved difficult, so Cheops’ son, Khafre, resorted to a clever trick. He built a smaller pyramid but constructed it on elevated ground. As a result, from a distance, Khafre’s pyramid appears much taller than the Pyramid of Cheops.

It’s very easy to distinguish between the two pyramids. The Pyramid of Cheops doesn’t have a capstone at the top. This capstone is the remnants of white limestone casing.

Once, all the pyramids of Giza were covered in white casing, which made them literally shine in the sun, stunning with their beauty and symbolizing the radiance of the god Ra.

The removal of the casing from the pyramids began with Muslims in the 13th century. Initially, it was used for building mosques. Then an earthquake struck Egypt, severely damaging Cairo. In need of construction materials, the Arabs intensified their dismantling of the pyramids.

The final resolution of the pyramid casing issue was carried out by Egyptian Pasha Muhammad Ali, who in the 1840s stripped the remaining casing from the pyramids and used it for the construction of the Alabaster Mosque in Cairo.

If the pyramids had reached us in their original state, they would be perfectly smooth and white, topped with a pyramidion—a capstone shaped like a small pyramid. Some pyramidions were covered with a layer of pure gold, which is why they were removed first, and there are few records of them.

Alas, all that remains of the casing is the yellowed cap of limestone slabs topping Khafre’s pyramid. It can be clearly seen from a vantage point away from the pyramids. From here, you can also see how much taller Khafre’s pyramid (in the center) appears compared to the Pyramid of Cheops (the farthest one). Yet, it is actually two meters shorter!

Next to the two giants stands a third pyramid. It was built by Khufu’s second son, Pharaoh Menkaure. This is the shortest of the three pyramids, barely reaching 66 meters in height compared to his father’s 138-meter pyramid.

Next to Menkaure’s pyramid stand three tiny pyramids, known as satellite pyramids. They were the burial places for the pharaoh’s wives.

Around the pyramids, there are numerous smaller tombs in the form of rectangular mastabas. These were used to bury various nobles, courtiers, and priests.

Thus, in Giza, one can see the entire history of the development of the Egyptian pyramid-building industry. In just 150 years, the Old Kingdom progressed from primitive mastabas to giant pyramids that even in the 21st century puzzle the minds of poorly educated people.

It’s a pity that this history cannot be fully appreciated by simply visiting Giza. It is too crowded and noisy here. However, all the “secrets of building” the Egyptian pyramids become clear if you start with Saqqara and follow the thought process of Imhotep.

Sphinx

Among the numerous large, small pyramids and mastabas in Giza, there is a unique object that exists as a single example: the Sphinx. It is the result of crossing a lion with a pharaoh, symbolizing the divine power of Egypt’s rulers.

In fact, it is not so unique. Thousands of sphinxes were erected throughout Egypt. The largest habitat of them is the Avenue of Sphinxes in Luxor. This avenue connects two massive temples, spans 2.7 kilometers, and is lined with 1,057 sphinxes.

However, in Giza, there is only one sphinx, which, due to its enormous size, is called the Sphinx. It was built by Pharaoh Khafre — the same one who outwitted Cheops with the size of his pyramid. The face of the Sphinx depicts Khafre’s own face, and it guards his pyramid specifically. It is Khafre’s pyramid, not Cheops’, that is behind the Sphinx in the iconic image of Egypt.

The face of the Sphinx is severely damaged. There is a legend that Napoleon’s soldiers caused this damage when they came to conquer Egypt, supposedly shooting at the Sphinx with rifles. In reality, there is no evidence that French soldiers fired at the Sphinx. Its broken nose is described in many documents long before that time. Most likely, a Muslim sheikh in the 14th century ordered the nose to be removed during his fanatical campaign against idolatry.

What is entirely true is the story that by the 20th century, the Sphinx was buried up to its neck in sand! However, neither Napoleon nor the Arab sheikhs had anything to do with this. Until archaeologists arrived, the Sphinx was simply of no interest to anyone, and it became covered by sand over the millennia.

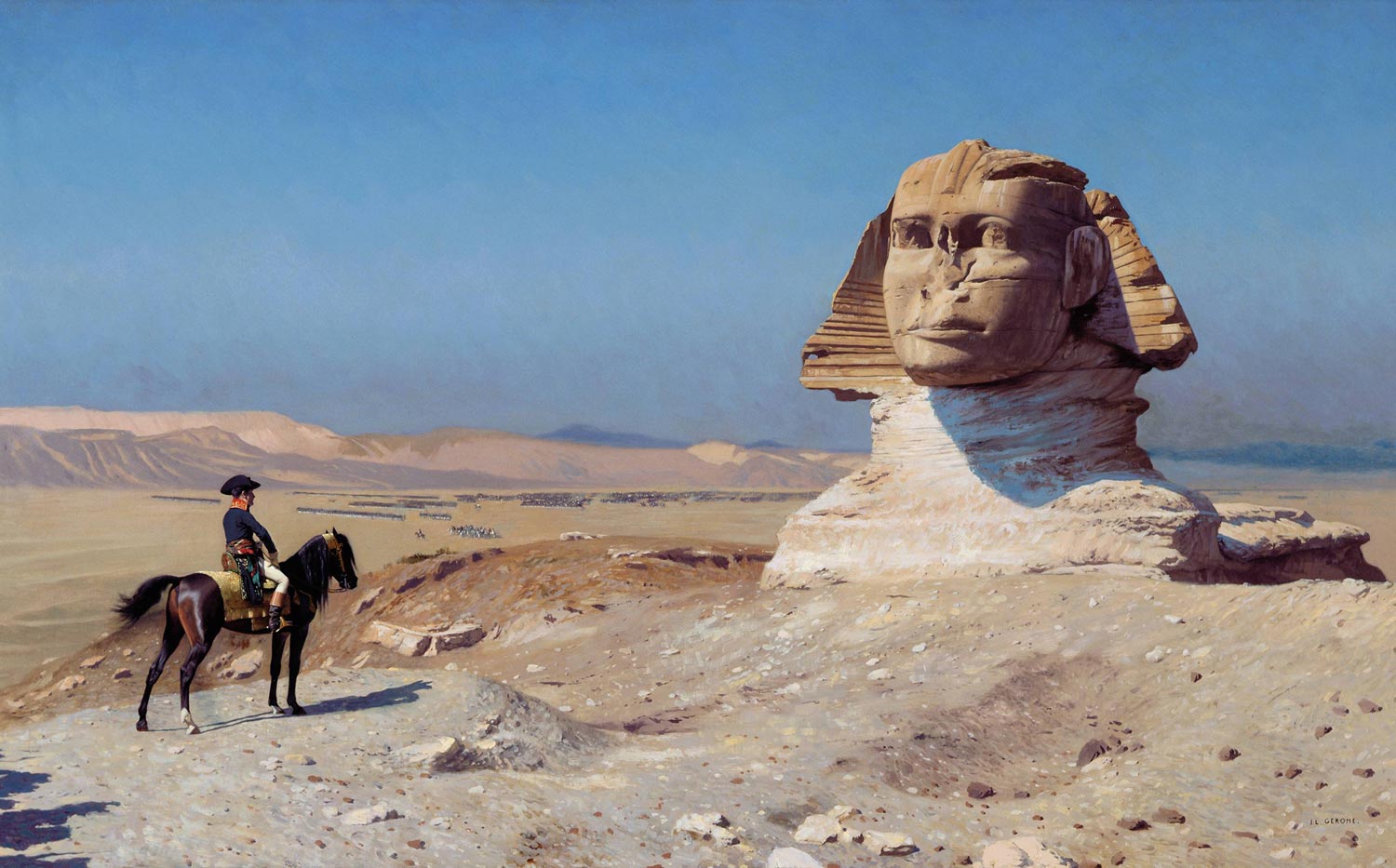

Not only have photographs of the buried Sphinx been preserved, but also a wonderful painting titled “Bonaparte Before the Sphinx,” in which Napoleon resembles the head of a warrior from Pushkin’s poem “Ruslan and Ludmila.”

When the Sphinx was finally excavated, its body was revealed to be enormous!

Today, this doesn’t surprise us. However, what shocked even the author was discovering that the Sphinx also has a tailed butt.

That’s it, I’m done.