Rome. Part One. Colosseum and Forum

I made my first solo trip in 2013. I remember stepping out of the airport and finding myself in hot summer Rome. I had no plan, no marked map, and no understanding at all why I had come here. I aimlessly wandered around the city under the blazing sun and hesitated to enter a restaurant to eat properly.

Having spent three days in Rome, I took with me two hundred photos of manhole covers, curbs, road signs, and trash cans. Among them was exactly one picture of the Colosseum, which I accidentally stumbled upon while walking around the city. I even managed to tie all this junk together into a short story.

It took quite some time to understand: Artemy Lebedev (a Russian traveller) is a bad example to follow. As for Rome, I offer my deepest apologies and start from where I left off last time.

Colosseum

Once the Roman Emperor Nero wanted to “live like a human” and decided to build for himself the largest palace in the world.

The emperor’s plans were hindered by residential houses and temples occupying the center of Rome — the most suitable place for a palace. Of course, Nero could have demolished the wretched hovels, but it was more difficult with the temples.

The famous Roman fire came to the emperor’s rescue, which burned almost the entire city, including the place where Nero planned to build his palace. Hearing about the fire from the morning news and greatly surprised by such a coincidence, the ancient Romans recalled the ancient Roman principle of cui bono — look for who benefits. And accused Nero of arson.

Nero too remembered this principle, accusing of arson the damned Christians, who at that time in Rome were roughly as much of a scare as Jehovah’s Witnesses now in Russia. Well, and eventually managed to build his palace on the ashes, with a golden dome and a 36-meter statue of himself; nearby, dug a lake — apparently, just in case of a new fire.

Amazed by such audacity, the Democratic Party Senate of Rome impeached Nero and declared him an enemy of the people. The final blow to the emperor was the news of naming a CD-burning software in his honor. Upon learning this, Nero committed suicide by cutting throat.

What Colosseum has to do with this, the reader may ask. Well, the thing is that the Colosseum was built right on the very lake that Nero dug for his palace. In fact, the whole Colosseum project is a pure example of ancient Roman propaganda!

After the fire, a financial crisis began in Rome. To build his golden palace, and by the way to restore the city, Nero significantly raised taxes. The patience of the Romans, who were first devastated by the fire and now robbed, finally ran out, leading to uprisings in the country. It was one of the worst periods in the history of the Roman Empire.

Nero’s suicide cheered up Rome even further. The Senate desperately tried to find a way out and changed emperors like gloves. After trying four old men for the gensecretary, the senators decided that only a true candidate from the people could fix the situation. They chose Vespasian — a talented pro-Palestinian general who earned popular love for crushing the Jewish protests in Israel.

Vespasian faced two tasks. Firstly, it was an urgent need to give the revolting people something to do. Secondly, it was essential to restore the tarnished authority of the Roman Empire after this zany Nero. But how to do this when the country is in such a crisis that has no even money to lay golden pathways at the senators’ dachas?

For long time ruminated Vespasian. Finally, he came up with a brilliant idea of how to sit on both chairs. He decided to demolish Nero’s palaces, fill in his lake, and build in their place... a giant stadium.

“And pay for everything will the Jews!” thought Vespasian in catch-up, and once again robbed Israel, taking away remaining treasures. Including the massive golden menorah, which can be found on the Arch leading to the Roman Forum.

Vespasian’s math was as follows.

Tortured of taxes and fires, Roman public demanded “bread and games.” The large construction project easily fulfilled the first demand. It is said that a quarter of Rome’s population was involved in the construction of the Colosseum. Everyone was busy: from architects to business lunch sellers. And were paid well, it was certainly enough for bread.

The idea of a large construction turned out to be so successful that two thousand years later, during the Great Depression, an American economist Keynes proposed a way to fight unemployment. According to him, to emerge from the crisis, the government must place a large and senseless order, providing employment for the unhappy proletariat. What was a great economist, made such a discovery!

However, the Colosseum wasn‘t senseless. Besides providing bread, it also offered games. What could be better for becalming riots than a free ticket to gladiator games? The Colosseum was open for all. Every Roman citizen could come to what he worked on for 10 years and witness the spectacular show. Meanwhile, the Colosseum could accommodate 50 thousand people.

Vespasian’s PR campaign was a great success. Weary of endless trouble times, Romans watched the gladiator games and dreamily imagined gouging out the eyes of the damned Nero.

Today, the Colosseum stands casually in the center of Rome. Just on one of the streets, beyond a regular pedestrian crossing, suddenly emerges a giant stadium, built two thousand years ago.

On the other side of the Colosseum is, roughly speaking, a wasteland with a boring Arch of Titus, and then begins the Roman Forum, overlooked by the Palatine Hill, which offers the best view of the ancient Roman stadium.

One still needs to climb up the hill. While we’re on the floor, the observer should know that the Colosseum is made up of an infinite number of arches of all shapes and sizes. They were not made for beauty. If the walls were made without arches, they would be too heavy, and the entire structure would collapse under its own weight.

In the original design of the Colosseum, there were 3 levels, and each level consisted of 80 arches. Inside, the Colosseum was designed like a layered cake: the walls that support the stadium’s seating are also composed of arches.

There, inside the Colosseum, it’s even more interesting than outside. Can be seen the remnants of the rows with marble seats. The front rows closest to the arena are the best preserved. Seating in the stadium was determined by social status: aristocrats sat in the front rows, while common folk sat in the back.

Only after Vespasian’s death the fourth level was added to the Colosseum, where gathered plebes, hobos, and slaves (these are different peoples), releseased for one day to watch the fight.

In the Colosseum‘s center was arena, where fights took their place.

Interestingly, the word “arena” comes from the Latin “harena,” which meant “sand.” So literally, “arena” is a place covered with sand. Nowadays, little remains of the arena, just a piece for tourists.

But that’s actually good because the most interesting parts were located beneath the arena. A beneath the arena lay the real Colosseum backstages. There were dressing rooms for the gladiators where they could powder their noses before a deadly battle. There were also cages with wild animals. This place was called the hypogeum.

The main feature of gladiator fight was that at any moment, in any part of the arena could spawn, for example, a lion. And the gladiator then had to fight the lion.

In order to have a lion suddenly appear in a random part of the arena, the Romans devised a clever system. In the new wooden arena, they created 60 trapdoors, each with a lift underneath. The animal was forced onto the platform, and the lift raised it up into the arena.

The English word “beast” is derived from the Latin “bestia,” meaning any wild animal. In Rome, gladiators who fought against animals were called bestiarii.

Bestiarii fought with all sorts of animals! The Colosseum saw lions, tigers, elephants, rhinoceroses, crocodiles, and even ostriches. Imagine the gladiator’s face when he turns around and someone secretly shoots onto the arena a hippopotamus.

Need I say that the Colosseum was a cutting-edge project?

Romans used concrete and red bricks in construction — lightweight materials that didn’t burden the structure heavily but maintained its strength.

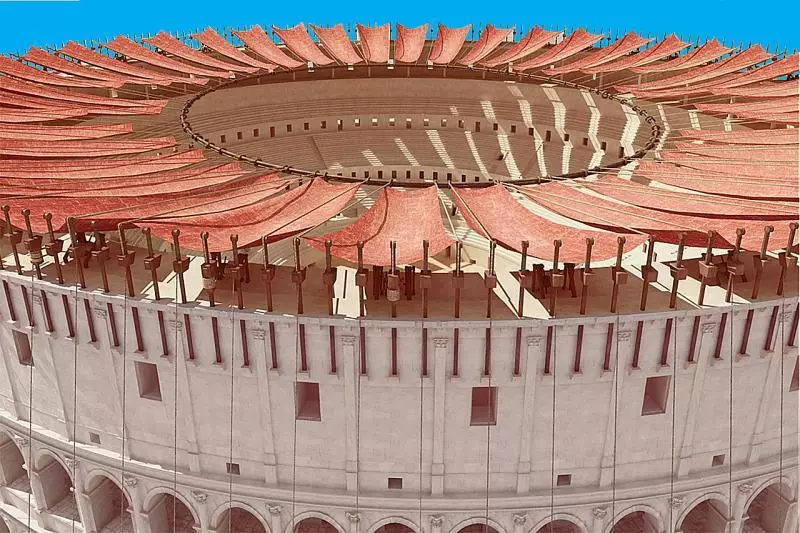

A feature of the Colosseum was its sunshades. In the heat, huge fabric awnings were stretched over the stadium, with ropes leading to a central ring, balancing themselves.

It is said that a whole team of specially hired sailors managed the awnings. Nowadays, nothing remains of the sunshades, and all details of the structure are still not precisely known.

Roman Forum

Behind the Colosseum is the Roman Forum. It was the main square of ancient Rome, which now lies in ruins.

On maps of Ancient Rome, one can find many inscriptions that start with the word “via.”

This Latin word meant path, road, and street. The reader knows it well if he can speak English. For example, the phrase “fly via London” intuitively means “fly through London.” Streets also go through the city.

The Roman Forum begins with a grand arch — the same one that depicts the golden menorah taken from Jerusalem. Behind the arch starts the main street of Ancient Rome — Via Sacra. If Romans spoke English, they would say it simply: Sacred Street.

When a Roman emperor returned from a great victory, such as in war, he would ride through the streets of Rome in a gilded chariot pulled by white horses, surrounded by senators and an orchestra.

The triumphant procession passed through the Sacred Street and halted at the temple of the god Jupiter. Here, to this most important god in the Roman Empire, they made a sacred offering. Hence the name of the street.

If a commander returned with a minor victory, such as over pirates, the procession walked without chariots and horses. After passing through the Sacred Street, the commander casually offered a sacrifice to Jupiter, and that was all.

The reader is well aware of both these ceremonies names. The grand procession with a chariot was called a triumph, and the minor — an ovation. Perhaps someone has also heard the phrase “memento mori,” which translates to “remember death.” These words were whispered in the triumphator’s ear during the procession to warn from thinking of himself as a god. How much we lack it now in politics!

Nothing left of the Jupiter’s temple where the sacrifice was made, but nearby preserved the walls of a similar temple of Saturn.

Interestingly, the best-preserved structures of ancient Rome are those that were rebuilt into churches. For example, one of the temples appears completely intact:

Upon closer look, it turns out that only the skeleton of the temple remains — in the form of columns. Its guts were long ago scraped out, and a Christian church was built around the bones.

Various arches are preserverd well: simple and sturdy structures. Other buildings in Rome decayed throughout the Middle Ages; they were dismantled for parts and repurposed for shops.

For example, in one of the most luxurious arches of the Roman Forum was a barbershop. The owner set up a bedroom in the upper part of the arch and cut a window in the wall to keep an eye out for thieves. This window gapes like a black hole right in the middle of a solemn inscription.

Despite all the efforts of medieval barbers, Rome outlived them all. From a good angle, it doesn’t even look like a ruin.

Tours with AR glasses become fashionable in Rome now, but it’s a waste of money. When one walks through the Roman Forum, brain itself completes the foundations and shards of columns. Vanished streets and erased houses are visually drawing up before your eyes.

The Roman Forum has something to see not only above but underground too. Rome was not the first to invent sewage systems. However, Rome was the first to build such a cool network of sewer systems that still operates to this day, although 2500 years have passed. Although now it carries no sewage, only rainwater.

The Roman sewage system served over a million city residents. It was an unimaginably complex project for that time. Humanity had never seen anything like it before. Under the city, kilometers of channels were dug to carry away sewage. Toilets in ordinary people’s homes were rare, but Rome had a network of public toilets located near markets, theaters, and forums.

By diverting sewage from all corners of Rome, dozens of small channels branched out and converged into larger ones, and then the waste merged in unison, flowing into the main sewer pipe of Ancient Rome. It was called the Great Cloaca — from the Latin word “cloaca,” meaning “sewer.”

Remnants of the pipes of the Great Cloaca can be seen. They protrude from the cut of the foundation.

But even more interesting than underground is to see Rome from a good height. And right next to the forum, there is such a height!

From a local hill, closely adjacent to the forum, the outlines of houses and streets are visible without any hints or schemes.

From here, one understands why Rome is the Eternal City.

From here, is finally visible the great Colosseum.

What height is this? This is the promised Palatine Hill, at the foot of which lies the Roman Forum.

Palatine Hill

Dozens of cities around the world are said to be built on seven hills, but only Rome can list all its hills by name.

The Palatine Hill was the central and the main hill of Rome. It housed the palaces of emperors and aristocrats. The Palatine is the most famous hill in the world, as it has inscribed itself in dozens of languages.

The thing is, the word “palace” in English derives from the name of this hill where the palaces were located: palace. In other languages, say in French, German, Russian and so on, the Palatine also left a trace in various words.

Now on the hill are beautiful gardens, with which the Palatine has been covered for one and a half thousand years of oblivion. These trees, which have become an unofficial symbol of Rome, are just one type of Italian pine. They may not be more than 500 years old.

Adjacent to the pines on the Palatine Hill grow ancient arches. They are a bit older: 2,000 years.

One of the largest buildings on the hill is the Palace of Augustus. It was built in 92. It‘s just a part of the massive Domitian’s palace, which is located in the very center of the Palatine Hill.

Not all ruins were once palaces. Nearby lie the remains resembling an ancient stadium. In reality, here was an imperial garden and a hippodrome.

However, this hippodrome is just a dwarf compared to the Circus Maximus — the main hippodrome of Ancient Rome.

Of course, it’s just a name. Circus Maximus wasn’t a circus in the modern sense. The Latin word “circus” itself simply meant “circle.” In Rome, this word was used to refer to any stadiums, hippodromes, and probably very fat people.

Circus Maximus is not the Palatine Hill whatsoever. It is located at its foot, on the other side of the Roman Forum. However, it was the Palatine from where revealed the best view of this hippodrome, which is now obscured by trees.

The scale of Circus Maximus is best seen from the ground. Only half of the stadium fits into the frame, and its end is barely visible. Chariot races were held here since the year of -500. During Julius Caesar’s time, the hippodrome accommodated 150 thousand seated spectators. Even the luxurious Meydan Racecourse in Dubai is designed for only 60 thousand people.

The remains of Circus Maximus are not very interesting. It’s just a field with the outlines of ancient walls. Italians often gather here for picnics.

From this field, one can beautifully see the ruins of the hill’s palaces. Exactly from these immense imperial chambers the Roman rulers watched the chariot races at the hippodrome.

But what did athletes, spectators, and bystanders watch from the stadium? They probably could barely make out anything besides a silhouette resembling Emperor Augustus. Therefore, they watched the races and didn’t even think that someday they would be able to enter the imperial palace for 20 euros.