Garbage City

On the outskirts of Cairo, there is an unusual district known as “Garbage City,” which is perhaps one of the dirtiest places on planet Earth.

Although numerous similar slums are scattered across Africa, India, and other impoverished regions of the planet, Cairo’s Garbage City stands out quite unusually among them. The fact is that beneath this garbage dump lies an entire history.

In Garbage City live Copts. They are direct descendants of the ancient Egyptians and representatives of a unique religious branch of Egyptian Orthodoxy. The history of the Copts begins back in the era of early Christianity, and to better understand them, we need to go back to the Roman Empire. Again.

Alexandria v. Constantinople

Alexandria has always been at war with Constantinople.

Long before Rome adopted Christianity, the main Christian community was located in the Egyptian city of Alexandria. This city still exists and is situated in the Nile Delta, where the river flows into the Mediterranean Sea. Today it is a rather poor city, but at the beginning of Common Era, Alexandria was a major cultural and scientific center. The city housed the Library of Alexandria, the largest collection of books in the ancient world, and the Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

The Church of Alexandria was one of the first Christian churches. According to legend, it was founded by Mark, one of the “twelve apostles” — the same one who is considered the author of the story “Gospel of Mark.”

Egypt, along with Alexandria, was already part of the Roman Empire at that time, but Constantinople was not even a consideration. This city appeared almost 300 years later and immediately began to annoy Alexandria. The Roman emperors declared it the new capital of the country. Eventually, Christianity became the state religion of Rome, and Constantinople took away all of Alexandria’s merits, becoming the new scientific, cultural, and religious center of antiquity.

It seems that as soon as Christianity lost its main enemy in the form of the pagan Roman authority, all its internal contradictions began to surface. The nature of Jesus Christ became the most heated question for several centuries, repeatedly pitting the religious views of Alexandria against those of Constantinople.

Today, most Christians adhere to the viewpoint that Jesus had two natures: divine and human, which are united in him inseparably but never merge into a single whole. This perspective is called dyophysitism, which translates from Greek as “double nature.” It is the official viewpoint of the Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant churches.

However, it was not always this way. Alexandria and Constantinople clashed numerous times over this debate. In Alexandria, rebellious priests frequently emerged, defending another perspective that can be conditionally called unitarian. One of these rebels was a priest named Arius, whose rebellion was so loud that even Emperor Constantine himself — the one who founded Constantinople — heard his cries.

Of course, the emperor did not need such disputes while he was busy developing the new capital. Therefore, he decided to convene a press conference, inviting at least a hundred of the most high-ranking priests and their sympathizers from all corners of the Roman Empire. At this gathering, the priests listened attentively to Arius’s arguments, respectfully labeled his views “Arianism,” and then declared him a heretic and ordered his exile. Interestingly, Alexandria played a decisive role in this, being categorically against its own rebels.

This gathering went down in history under two names: the “Ecumenical Council,” because priests from all over the then-known “universe” attended it (oecumenicus means universe in Latin), and the “Council of Nicaea,” because it was held in the city of Nicaea.

However, the main achievement of the Ecumenical Council was not the condemnation of Arius but the adoption of a unified view on the nature of Jesus. The council officially affirmed that Jesus possessed not only a human nature but also a divine one. And it not only affirmed this but also prohibited thinking otherwise, declaring its view the only correct and universal one. Thanks to this decision, the Greek word for “universal” entered all languages of the world and became the name of the largest Christian church. The reader undoubtedly knows this word. It is pronounced “katholikos.”

Another success of the Ecumenical Council was the establishment of the “Nicene Creed” — the Christian equivalent of the Islamic Shahada. Generally speaking, every Christian should know its text by heart to be considered truly faithful. But, as is customary in Christianity, this doctrine was swept under the rug.

Thus, as a result of the Ecumenical Council, Arius was exiled. Alexandria had won. However, the story of Arianism was only beginning. Just three years later, Emperor Constantine realized that a religious split was starting in the empire, so he hastily reinstated Arius and his followers from exile and imprisoned a couple of their opponents instead. When Constantine died, his son Constantius became emperor and suddenly made a Christian coming-out by declaring himself... an Arian. Then those who had previously exiled Arius found exiled themselves.

But even that was not the end of it. After Constantius, Julian became emperor, and he went all-in by announcing the abolition of the state religion, the return of the Roman Empire to paganism, and material benefits for everyone who renounced Christianity. Fortunately, this absurdity lasted only two years, after which Julian kicked the bucket while trying to conquer Iran.

To somehow restore order in the empire after such upheavals, the next emperor, Theodosius, decided to convene the Second Ecumenical Council. This council once again condemned Arianism, affirmed the concept of the “holy trinity,” and made a few minor amendments to the Nicene Creed.

The breach in the hull of the Christian ship was patched for about half a century. A new round of church bickerings was ignited by a priest named Nestorius. Unlike Arius, who came from Alexandria, Nestorius was the Archbishop of Constantinople. Because of his high position, his teachings gained significant popularity in the city and provoked intense hatred from Alexandria.

Nestorius was an astonishing personage who managed to miss both seats at once. On one hand, he opposed Arianism and maintained that Jesus certainly had a divine essence. On the other hand, he asserted that Jesus was initially born human, and only later did his divine nature absorb the human one. Taking this idea further, Nestorius went so far in his preaching as to call the “God-bearer” Virgin Mary... the “Human-bearer.”

Then it kicked off! All Roman popes got aroused at once. Some Cyril of Alexandria demanded that Nestorius take his words back within ten days. Others called him Judas. In short, another split was brewing in Christianity. And what did the next Roman emperor do? Correct, he convened yet another Ecumenical Council, the third one, which declared Nestorius a heretic and sent him into exile. That’s how his teachings went down in history as Nestorianism.

Alexandria triumphed for the second time, but it ultimately took a total of six Ecumenical Councils and three hundred years of debate to sort out all this religious confusion. The central question was: Who exactly was Jesus: God, man, God-man, or man-God — and if the latter, in what proportions?

Despite this, neither Arianism nor Nestorianism was completely eradicated. Both have survived to the present day. For example, Jehovah’s Witnesses similarly reject the trinity and consider Jesus to be an ordinary man, not the son of god. Of course, they deny any connection with Arianism.

So, boys and girls, if you like the ideas of Mr. Arius and live in Russia, don’t tell anyone about it. Seventeen hundred years later there, people are sent to exile as they were in the times of Emperor Constantine.

Copts

But back to our Copts.

The fierce struggle of Alexandria against Nestorius led to the emergence of yet another movement in Christianity — monophysitism. The monophysites were fervent opponents of Nestorianism and believed that Jesus had only one nature — the divine-human. They argued that if Jesus had two natures, it would mean he remained internally divided.

It might seem, what could be more logical and elegant? Alexandria thought so too, as it officially supported the Monophysite perspective. But this time, the priests of Constantinople rebelled, insisting that Jesus consisted of two distinct natures — divine and human — but united in one person. A colossal difference!

Due to this subtlety, in which the reader might now struggle to grasp the meaning, the priests convened the Fourth Ecumenical Council, where they declared the Monophysites heretics. This time, Constantinople won. But here the unstoppable force met an immovable object: Alexandria refused to accept this decision, and several churches followed its lead, including the Armenian, Georgian, Syrian, and Ethiopian Churches.

That’s right, dear friends. If you’ve ever wondered how Orthodoxy in Georgia and Armenia differs from Orthodoxy in Russia, here’s the answer: they are Monophysite churches, meaning heretical churches. Fortunately, religious dogmas are once again were let slide, so the Russian Church pretends it’s all good and maintains friendship with the Georgian and Armenian ones.

The Alexandrian Church itself split in two. One part eventually accepted the council’s decision, but there remained a second part that still adheres to the Monophysite view. This part is exactly what’s known as the Coptic Church.

The word “Copt” emerged after the Arabs conquered Egypt, referring to its native inhabitants as Copts. Although the number of these indigenous people in Egypt significantly decreased following the Arab conquest, they did not disappear entirely. Today, there are as many as 10 million Copts living in Egypt. It is they — not the Arabs! — are the descendants of the true ancient Egyptians who once built the pyramids. And it’s to them where we finally depart to.

Garbage City

In Egypt, Copts live everywhere, and Garbage City is just one of the Coptic neighborhoods in Cairo, not the only “Coptic ghetto” in the world. It is home to 250,000 people, almost all of whom are Copts. And their occupation is collecting garbage.

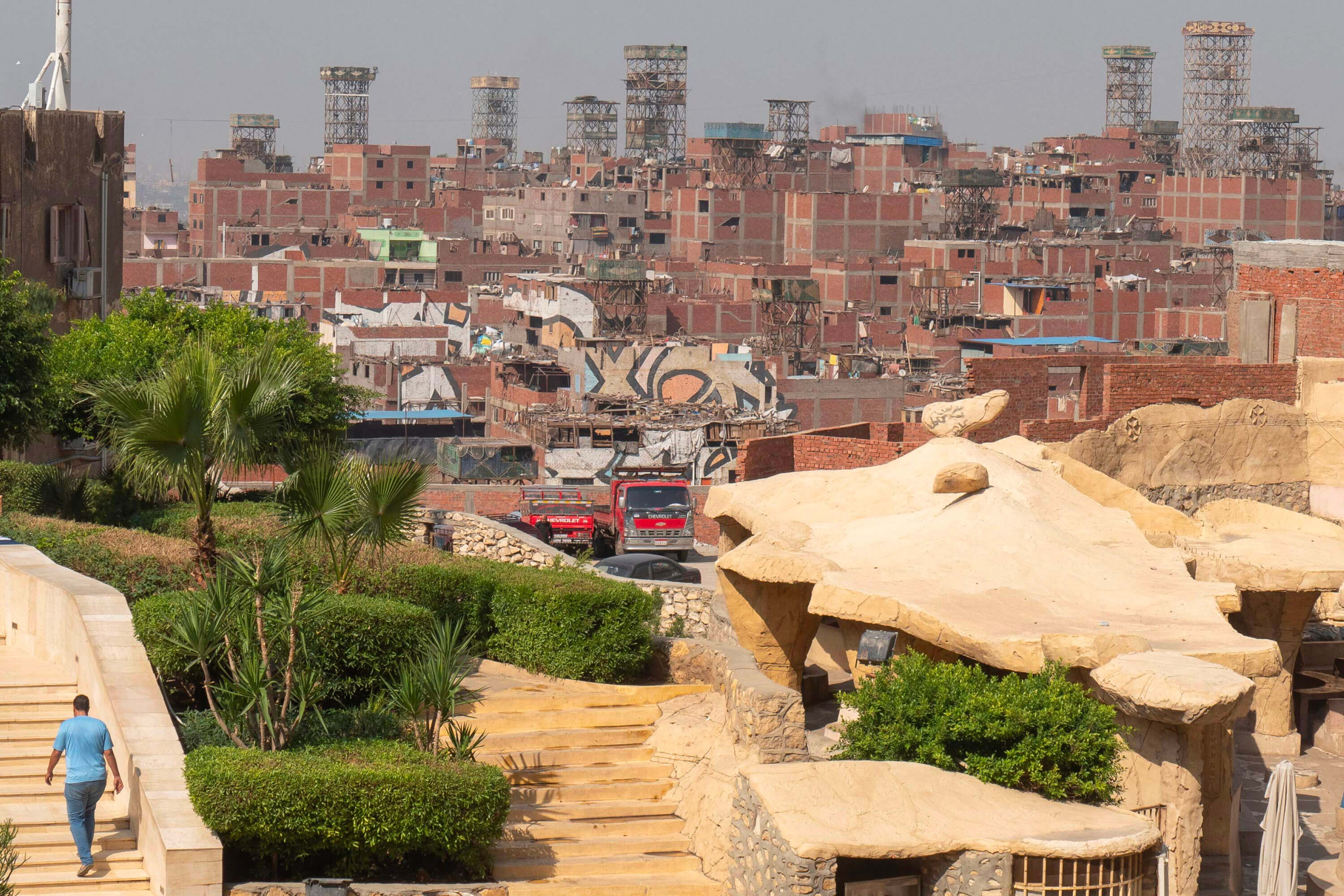

At the very entrance, Garbage City hardly differs from the rest of Cairo. It’s the same general Egyptian sketchiness.

As you move further into the area, you start to see more and more vehicles loaded to the brim with bundles.

A little further in, and you’ll find all the sidewalks piled with bags, while sunlight has to pierce through a dusty haze enveloping the entire area.

The bags, of course, contain garbage. And the Copts collect it. It so happened.

A hundred years ago, Garbage City was just one of the neighborhoods of Cairo, but in the 1930s, migrants from southern regions of Egypt began to arrive. They came from farming families, but over time, agriculture could no longer sustain them, and they went to Cairo in search of work.

They found work, but it was far from STEM. They had to take up garbage collection — the dirtiest job, one that even poor Cairo Muslims didn’t want to do. That’s how the migrants got their name: “zabbaleen,” which translates from Arabic as “garbagemen.”

Today, Copts in Egypt face no restrictions, and many of them live in nice, affluent areas. However, the descendants of the zabbaleen have been unable to break free from this ancestral curse for almost a hundred years. The cursed garbage that their Coptic granddads fought with, is now collected by their children.

In another twenty years, they will be replaced by their grandchildren, who are growing up amidst this dump and preparing to take on the family legacy.

There will be enough garbage in Garbage City for another hundred years, as it flows in from all over Cairo. The garbagemen pick it up themselves from homes, shops, restaurants, and offices in Cairo and bring it here, where it’s first sorted... and the further fate of the garbage depends on its type. Plastic, for example, is compressed and bundled.

The same is done with soft metals like tin cans. Bundled cubes of crushed cans, coca-colas, and green peas are neatly lined up along the streets of Garbage City.

In this form, the garbage is then sent for recycling, or something simple is made from it on-site and sold. There are usually no problems with plastic and metal. However, dealing with food waste is much more complicated. Even if packed into dozens of plastic bags, they will still break through and smell so bad that they attract swarms of flies.

Some of the food waste is turned into compost and sold as fertilizer by the zabbaleen, but most of it is fed to their pigs, which graze right on the roofs of their homes and voraciously consume the rotting dump.

These animals eventually become part of the food chain themselves. They are slaughtered and sold in local shops. Sometimes, you might see a skinned carcass hanging outside in thirty-degree heat.

Of course, the zabbaleen don’t have any magical immunity. About 40% of this city’s residents suffer from hepatitis. But getting rid of these unsanitary conditions isn’t easy. During the swine flu, the Cairo authorities slaughtered countless pigs — only to end up with mountains of garbage and no one left to gorge it.

However, the zabbaleen keep not only pigs but also other animals, such as donkeys, which are used to transport bags and also operate on waste.

However, the majority of the garbage collectors’ work involves manual labor.

There’s no talk of technology in Garbage City. All the waste, whether it’s plastic, metal, paper, or refuse, is sorted, sifted through, washed, cut, pressed, crushed, or recycled.

The manual labor of the zabbaleen is much cheaper than any automation, and their efficiency is exceptional. While most companies in Europe recycle only 25% of waste, the zabbaleen manage to recycle as much as 80%. In total, they handle 14 tons of garbage... every day! And this is nearly all the waste discarded in Cairo.

Walking through Garbage City is reminiscent of a tour of the tanneries in Morocco. There’s the same unbearable stench that can make you almost vomit at times. As a bonus, trucks loaded with garbage speed along the roads, constantly dropping and dripping things.

Local residents react in different ways. Some offer to take a photo together, while others shout unpleasant things after you. Newspapers have reported several instances of zabbaleen attacking tourists. Naturally, in the age of the internet, everyone understands that tourists are looking for shock content and then mock the dire conditions of these impoverished people.

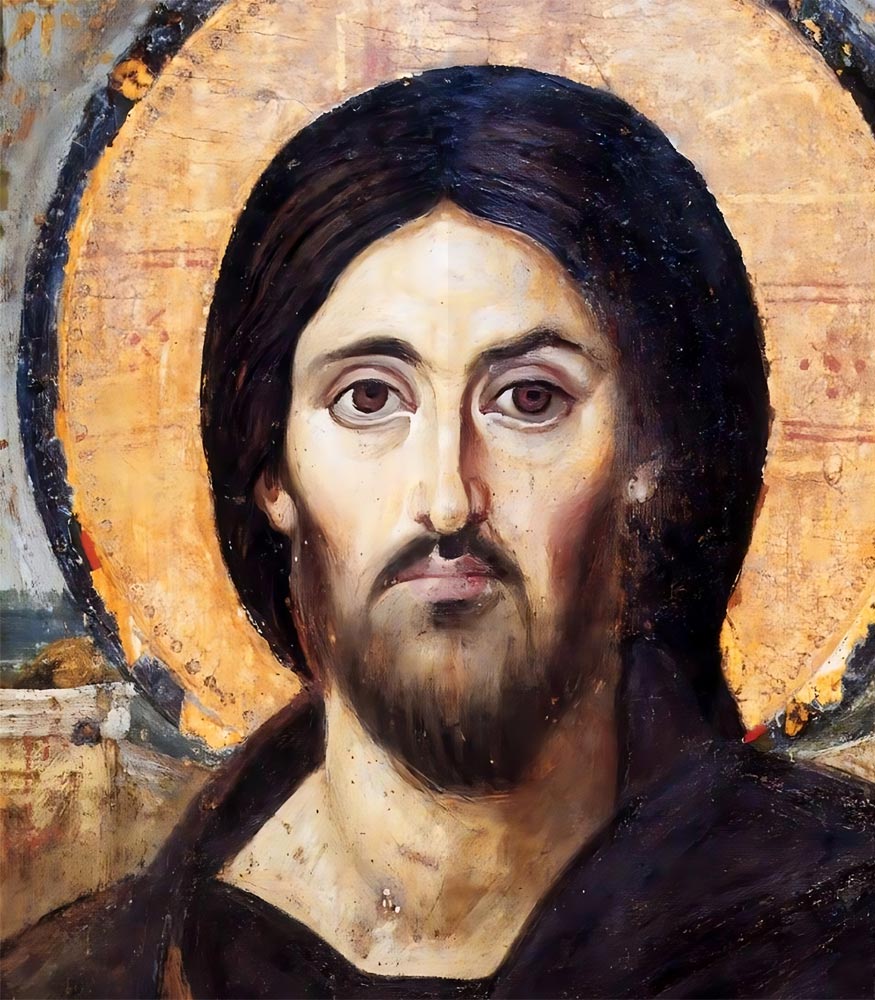

Is there another reason to visit Garbage City? Perhaps, amidst the piles of garbage, the reader might not have noticed that some photos feature religious posters, like these:

Sometimes, you can spot crosses and other Christian symbols on the houses.

Sometimes an icon of the Virgin Mary holding Jesus hangs right at the entrance to a garbage workshop.

Sometimes the Holy Mother gazes down from the heavens, nestled between two rows of laundry hanging on clotheslines.

Such posters can be found throughout Garbage City.

These awkward drawings are part of Coptic identity. Living as garbage collectors is dreadful, so the Coptic community tries to find some support in their difficult situation. There are several churches in the city, and the posters of the Virgin Mary at every turn perhaps provide some comfort to help them get through another day.

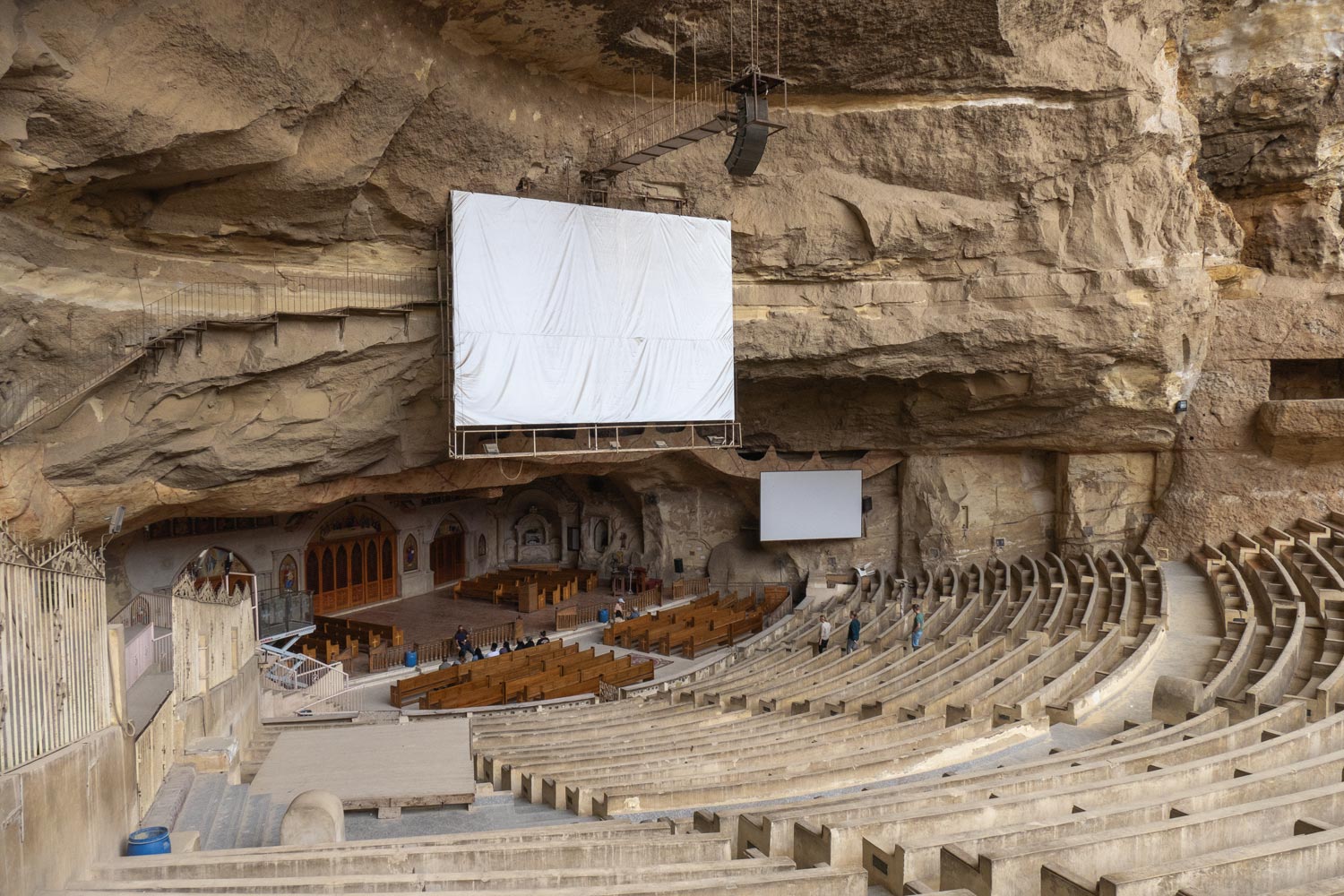

Garbage City is located at the foot of a small mountain. At the top of this mountain, lies a large monastery.

Behind the monastery’s facade lies a cave church, carved directly into the mountain and shaped like a Roman amphitheater.

The walls of the mountain itself are adorned with religious drawings.

If you don’t know the history of this place, you might easily believe that this monastery is a thousand years old. In reality, it was built in 1974 with funds from the Coptic community, accumulated over the years from processing waste. It’s amazing what people can achieve in their efforts to preserve their identity.

From the terrace in front of the monastery, opens a view of Garbage City.

It is monstrous.

Even the rooftops of residential buildings are piled with bags of garbage, and heaps of rotting waste gape in the gaps between the structures.

From here, you can also see goats being raised right on the rooftops of houses. It seems that they, like the pigs, feed on refuse. It’s unlikely these unfortunate animals have ever been down to the street or seen green grass.

The monastery itself is named after Saint Simon the Tanner.

According to legend, when Egypt was already under Muslim rule, the caliph decided to hold a contest. The caliph’s advisor quoted the Gospel: “If you have faith as small as a mustard seed, you will say to this mountain, ’Move from here to there,’ and it will move.” With these words, he challenged the Coptic priest to move the very mountain on which the monastery stands today — or else he would order to kill all Copts.

Not knowing what to do, the priest sought out Saint Simon, who was known for delivering water to the poor in leather bags. Simon whispered to him to say “Lord, have mercy” three times and make the sign of the cross over the mountain. When the priest spoke these words, the mountain rose and moved to a new location.

Unfortunately, this is just a legend. The only mountains the Copts move today are mountains of garbage. And they move them not with the sign of the cross, but with the help of donkeys and homemade lifts.

As for Saint Simon, he disappeared right after that — and never was seen again.