Kosovo

“Good evening. I’m in Kosovo and my roaming isn’t working.”

“Please clarify, is that in Russia?”

“Nah, geez! In Serbia!”

The intercity bus from Belgrade to Pristina traveled for four hours until it reached a checkpoint adorned with a large blue flag.

On the flag, instead of an eagle, cross, or any other national symbol, was a strange amorphous brown blotch resembling the borders of some region.

The bus doors swung open, and a uniformed employee entered the cabin and began checking documents. None of the passengers aroused suspicion until it was my turn. Upon seeing my maroon passport with a double-headed eagle, the inspector widened his eyes in surprise and froze.

“Hooray, it’s Kosovo!” echoed in my mind.

Pristina incident

My passport was taken; I was escorted out of the bus and led to a small window. The inspector disappeared somewhere, and I was handed over to the warm hands of the chief border guard. He gave me a stern look, glanced at my passport, and said:

“Andrew?”

“Yes sir”

“Welcome to Kosovo”

To travel to Kosovo in September 2022, when the war with Ukraine was in full swing and Russians were afraid of even in Germany — that was a brilliant plan. Reliable as Swiss watches.

But while all the newspapers wrote about the entry ban to Latvia, Czech Republic, and Poland, I never heard anywhere that Russians were being denied entry to Kosovo. Perhaps Kosovars never even thought of specifically prohibiting them because you would have to be a complete moron to come here.

The border guard continued:

“Andrew, may I ask what brought you to our abode?”

“Sir, the thing is, I am a traveler, a collector of Serbian lands. My goal is to visit every country in the world. And so, being in Serbia, I decided to go to Macedonia. And your wonderful country lies between these states!”

Upon hearing the word “country,” the border guard instantly melted away: Russia has recognized the independence of Kosovo!

“Alright, Andrew. How many days do you want to stay in our country?”

“Exactly one day, sir. On Sunday, I will already be flying from Macedonia to Greece. Here is my plane ticket.”

“And what do you want to see during this time?”

“Only Pristina. Nothing else.”

“Well, since it’s only Pristina... Here is a form for you to fill out.”

The border guard handed me a typical European questionnaire, similar to the one filled out when applying for a Schengen visa. I filled it out, and the border guard read it, sniffed, and stamped my passport with a Kosovar stamp.

“Here you go. And remember, Andrew, I will call your hotel and ask them to keep an eye on you.”

“Ne problema!”

The interrogation lasted half an hour. The bus, packed with passengers, stood and waited the whole time. When I appeared in the cabin, applause broke out. I took my seat, and was bombarded with questions.

“What happened, why did it take so long?”

“Well, here’s what happened, look at my passport”

“Is this Russia? And all this because of that? What a disgrace to discriminate on nationality!”

“Well, Russia and Kosovo have a complicated history...”

“Yes, but it’s all politics! Regular people shouldn’t suffer. Why are you coming here, do you have friends in Kosovo?”

“No, I’m a traveler. Look at how many stamps are in my passport. I collect countries, and I decided to come to yours”

“Wow. Well then, welcome!”

To be honest, I expected the Kosovars to come at me with fists. After all, it was my country that provoked the famous “Prishtina incident” in 1999, which almost led to a war between Russia and NATO.

Packs of wolves

Once upon a time, Voyageurs National Park in Minnesota decided to investigate how wolf packs divide their territory. They attached GPS trackers to seven wolves from different packs. Data analysis revealed that the wolves do not venture beyond their pack’s territory, and these territories have clear boundaries.

Probably, if people were animals, they would also settle within the boundaries of their packs and fight only because of hunger. But with humans, everything is much more complicated.

Evolution has given humans abstract thinking. Unlike wolves, who recognize each other by smell, humans distinguish between their own and strangers not only by external characteristics. People of different skin colors, facial features, and origins come together based on an abstract idea that doesn’t even exist in the real world. For example, based on religion.

Long ago, humans used to unite in communities based on kinship. These communities gradually expanded, incorporating neighboring tribes and becoming the first semblance of states. Uniting based on kinship became increasingly complex, and more abstract ideas of unity took their place: territory, language, traditions, culture, religion, ethnicity.

Ancient Rome went the furthest. Conquering half of the world and subjugating dozens of peoples, Rome was the first to come up with an abstraction that could unite different cultures, religions, and ethnicities. Rome invented citizenship in its modern understanding. For the first time, anyone living in the Roman Empire, unrelated to the actual Romans, could become a citizen of Rome. At the same time, they retained their belonging to their own tribe. The Gauls, Egyptians, and Greeks conquered by Rome remained Gauls, Egyptians, and Greeks. But in addition, they also became Romans!

This dual identity is a characteristic feature of empires. The problem is that empires often forcibly relocate and mix subordinate peoples. As long as the empire is alive, this process does not lead to conflicts, but it becomes a time bomb. Empires have a tendency to disintegrate, taking with them the newly created identity. Peoples deprived of imperial unity must return to their ethnic idea and restore their historical borders. But how can they do so when the borders have long been erased, and the wolves of all packs are mixed?

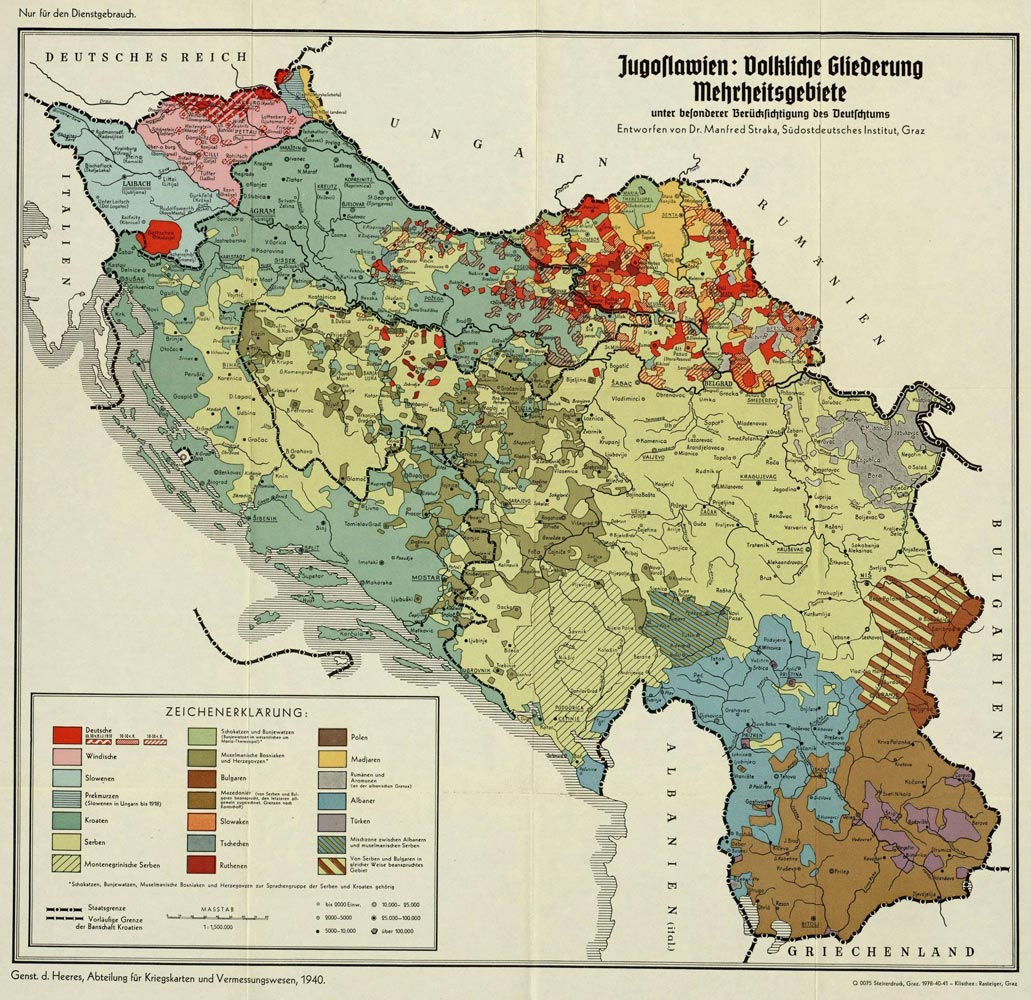

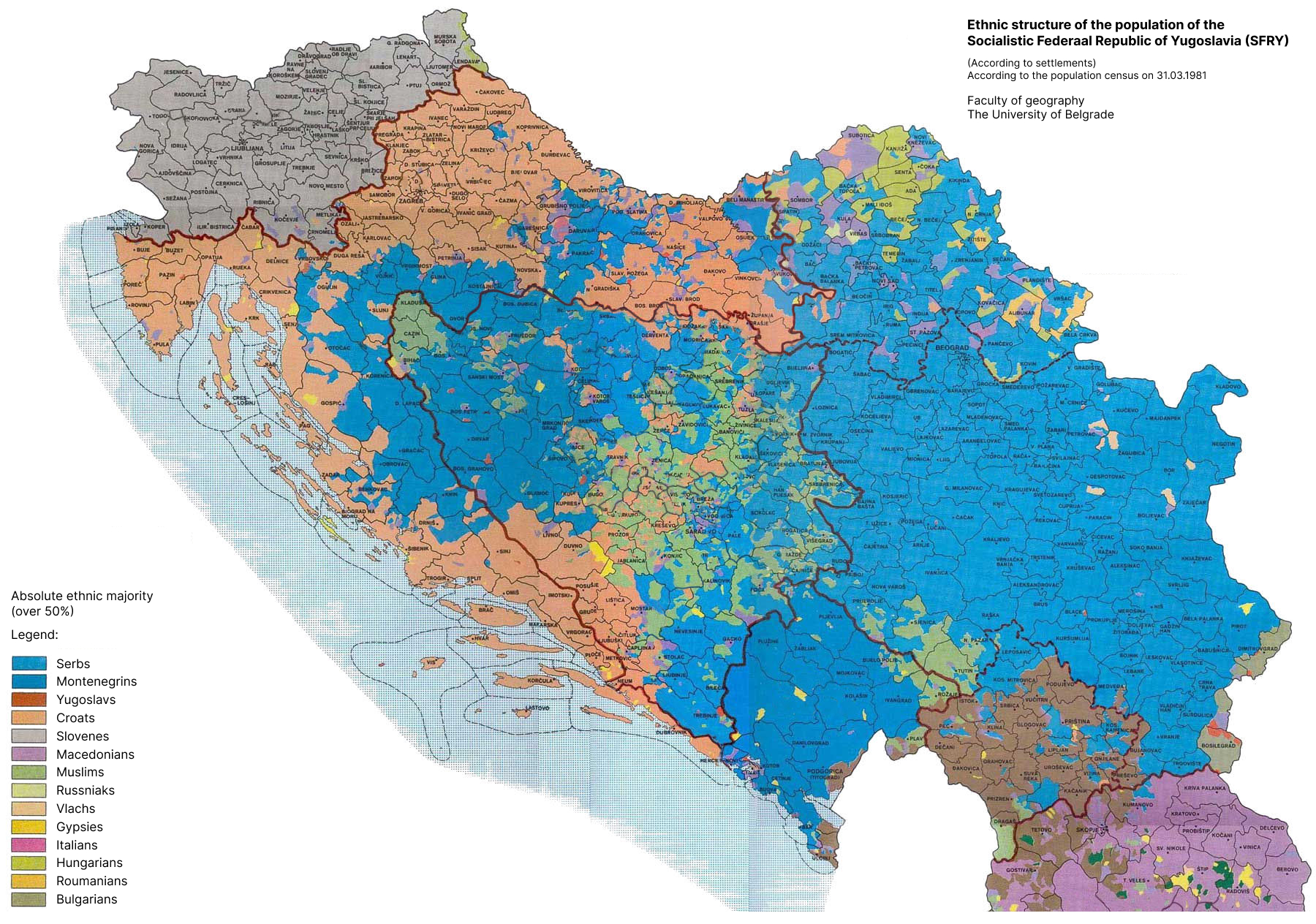

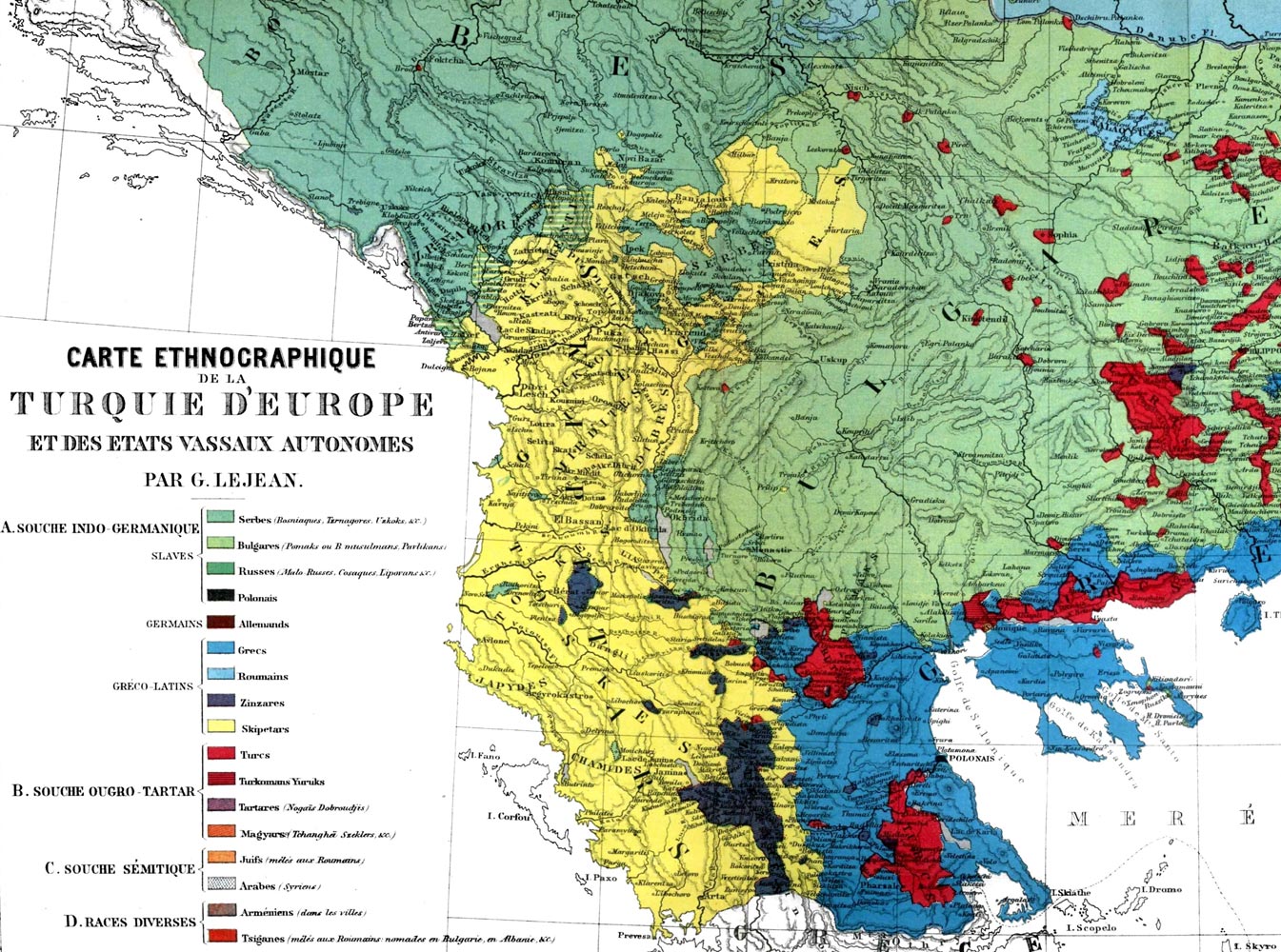

Let’s take the Balkans. On this German map, it is evident that in the 20th century, peoples mixed to such an extent that drawing borders between them became simply impossible.

Once, a large part of these peoples lived within empires, but then came the First World War and the empires ceased to exist. Slovenia, Bosnia, and Croatia emerged from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, while Kosovo and Macedonia separated from the Ottoman Empire.

Serbia gathered the fragmented lands around itself, naming the new country the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and creating a new imperial identity. Now Bosniaks, Serbs, and Slovenes also became Yugoslavs.

“And since they are all now one people, they don’t need national territories,” thought the King of Yugoslavia and divided the country in such a way that the boundaries of the regions did not coincide with the places of ethnic settlement.

Such division is only possible with a strong central authority that governs the regions of the country from the center. The center of Yugoslavia was in Belgrade, so it appeared as if Serbs colonized and governed all the other peoples. Naturally, the regions began to protest.

Then the new leader of Yugoslavia, the sun-like headman Josip Vissarionovich Broz Tito, decided to reduce the level of Serbian nationalism and transformed the kingdom into a federation. The regions gained greater autonomy, and their boundaries now roughly corresponded to the actual areas where the peoples lived.

Of course, Tito wasn’t a fool. He understood that the national regions could declare their independence. Therefore, he continued to mix the wolves among the packs and, for example, generously funded the moving of Albanians to Kosovo, and left some Serbian regions in Bosnia: it still would be very hard to separate them.

And everything would have been wonderful for the Serbs. They would eat their pljeskavica and stroll around Fruška Gora. If only on the right side of the map didn’t blow up the USSR. Prosperous and wealthy Yugoslavia suddenly ceased to be prosperous and wealthy because it lost its largest market for selling lacquered trunks.

Fair-haired comrade Tito had already dropped off his Yugoslavian hooks, and Slobodan Milošević was in control of the country. Hmm, how did they elect him if he was jailed in The Hague? Well, never mind.

In general, the impoverished Yugoslavia led by this Milosevic cracked along the exact those national seams by which our Serbian friend Josia divided the country. But despite all the curses directed towards Tito, I would argue what’s better: to break apart along the ready borders or to start drawing them during the collapse. If Yugoslavia had been divided as it was under the king, the civil war would have been 10 times more civil.

Thus, from Yugoslavia, one after another — some peacefully, some through conflict — exited all federal republics. As for Kosovo... It’s strange how much attention is given to it. Before the breakup, only Albanians lived there, and it wasn’t even designated as a separate republic but directly included in Serbia. Even on the map of 1861, it can be seen that there was a Serbian enclave surrounded by Albanians in Kosovo.

Dear reader! I want to state that the entire “Kosovo issue” is not worth a bit of cevapcici. Kosovo’s secession marked the end of the long-standing disintegration of Yugoslavia, which could have started earlier. Kosovo was actually the least Serbian region and its last connection to Serbia was during the Mongol-Tatar yoke.

Milosevic was indeed a bastard. By the time NATO started bombing Belgrade, the war he unleashed in an attempt to forcefully preserve Yugoslavia had already been going on for almost 10 years. This war had already took the lives of 100,000 people and ethnic cleansing was taking place. After his defeat in Bosnia and a pause, Milosevic took up arms with renewed force, this time for Kosovo, a tiny and impoverished Albanian region on the outskirts of the country. It was only then that Belgrade was truly targeted for bombings, and it was successful: the war came to a halt.

Now another psychopath, Putin, loves to refer to some “Kosovo precedent” to justify the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbass. But this whole “Kosovo precedent” is pulled out of thin air, and Ukraine has never experienced ethnic cleansing, had Russian enclaves, or a war between two empires.

Serbs themselves regret only that Milosevic was disgracefully tried in the foreign Hague. As if the courts in Belgrade were worse, boy that’s offensive.

Pristina

From the border, it took just an hour for the bus to reach the capital city of Kosovo, Pristina.

Kosovars turned out to be friendly towards Russian me. My neighbor accompanied me to the bus station and invited to a decent café, where he treated me to Italian coffee at his own expense. After that, he put me in a taxi and explained to the driver where to go. The taxi driver, of course, overcharged me, but that’s what taxi drivers do. However, my jaw dropped when he started speaking broken Russian. In the midst of the war! In Kosovo!

Pristina itself also turned out to be a surprisingly pleasant city. I arrived there in the evening. A long garland was hanging over the main city avenue, even though New Year’s was still far away.

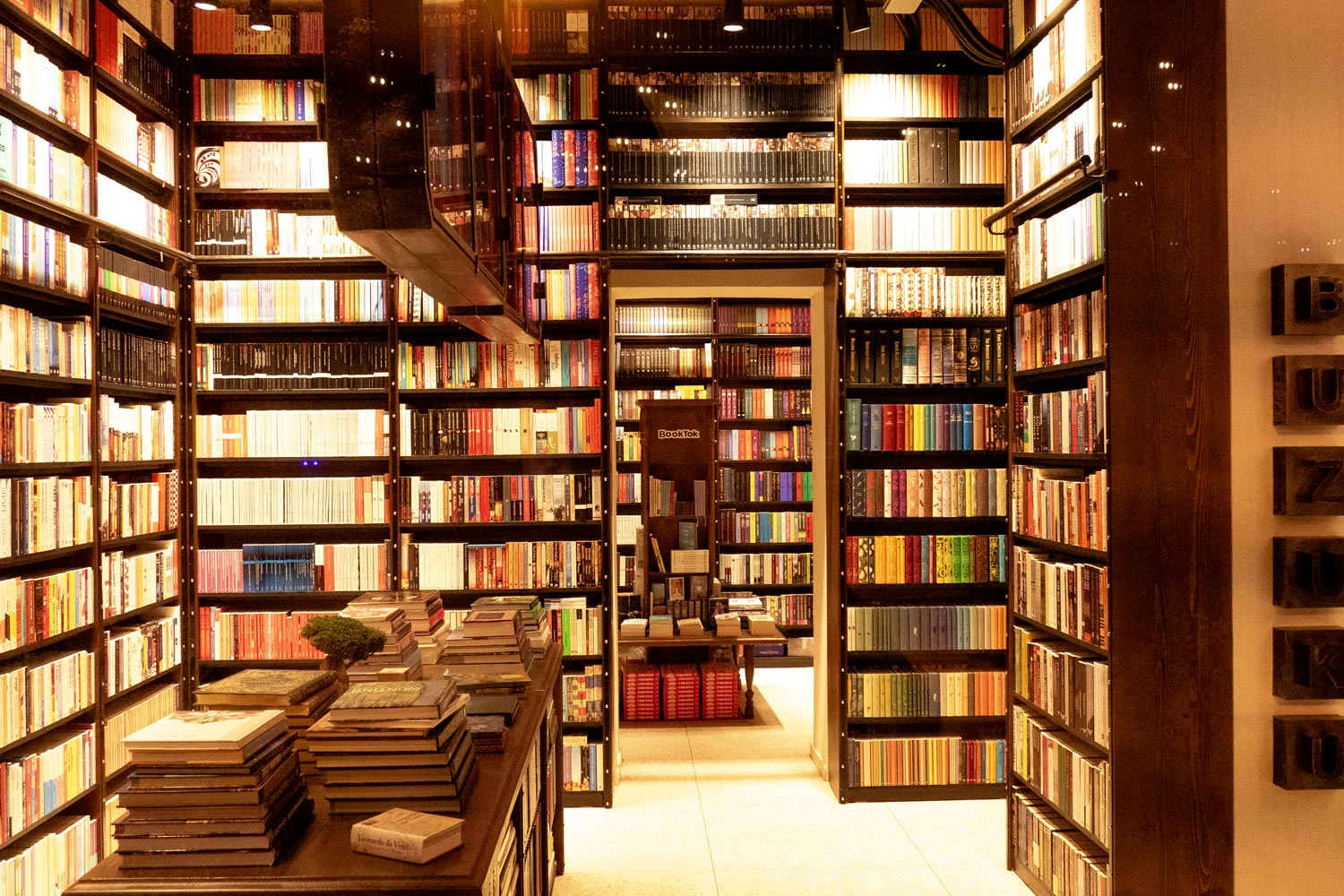

Along the avenue, dozens of establishments were operating: cafes and bars, jewelry stores, currency exchange offices, bookshops, and hotdog stands.

At the end of the avenue, it led to a small circular square where a residential high-rise building stood with a glowing star on someone’s balcony. That little star firmly settled in my mind and completely melted my Slavic heart. The remnants of worry faded away, and Pristina immediately became incredibly warm and welcoming.

In the morning, the avenue turned out to be just as good.

In Kosovo, I found what I came to Serbia for — delicious Balkan food. Unlike Belgrade, Pristina is full of excellent restaurants where you can have a good meal for 5 bucks. They are all located in the alleys branching off from the main avenue.

Due to the war and immigration, Kosovo has a high population of young people: individuals under 30 years old make up 65% of the country’s population. It is these young people who stroll along the city streets, creating a very pleasant atmosphere.

Of course, it’s not Europe. Something indescribably Albanian constantly flashes here and there.

The pillars covered in memorial leaflets shatter the mirage completely: this is the Balkans. Such leaflets are hung everywhere in Yugoslavia and Bulgaria to inform as many people as possible about a death, just in case someone knew the person and was not informed.

Depending on the country, the sheets differ either by the symbol of the religion the deceased practiced or the color of the frame. A green border means that the person was a Muslim, and a red one means atheist.

At the other end of the alley stands the government building, which doesn’t even seem to be guarded. Strange, because the government of Kosovo is one of a kind. The former president is right now being tried in The Hague for war crimes.

Next to it, suddenly appeared a memorial to the victims of September 11. Kosovo owes its creation to America, so Kosovars mention the USA on every occasion.

A bit further, ordinary residential yards begin. The mosque reminds us of the times of the Ottoman Empire: Sultan Suleiman was the first to disguise nuclear warheads as minarets.

The typical streets in the old district of Pristina resemble Albania. Mostly low-rise buildings are predominant here.

In this neighborhood, stands the only Orthodox church in Pristina — the Church of St. Nicholas. It was built in 1850 and has been attacked multiple times. There are about 200 Serbs living in Pristina, and they make up about 6% of the population in all of Kosovo. In addition to the Orthodox church, there is also a Catholic church and several evangelical ones in Pristina.

The other part of Pristina is more modern and built with quite eerie high-rise buildings.

These houses are unimpressive, many of them are unfinished, but overall, they are typical “human anthills” of Eastern Europe.

Occasionally, slightly more well-maintained landscapes can be found, but it is clear that people live here not very affluent, to put it mildly.

Among these panel buildings is the main attraction of Kosovo — Bill Clinton Boulevard.

America provided incredible assistance to Kosovo and was the first to recognize the independence of the new country. During the war, the President of the US was Bill Clinton, who became an icon for Kosovars. In his honor, they named a boulevard after him, and a huge portrait was hung on one of the buildings.

In October 2009, a bronze monument with the American flag was installed beneath the poster. Bill Clinton himself attended the opening ceremony.

I still don’t understand why they chose to unveil the monument right here. Amidst the dilapidated panel buildings it looks quite comical. On the other hand, I found an insane graffiti nearby.

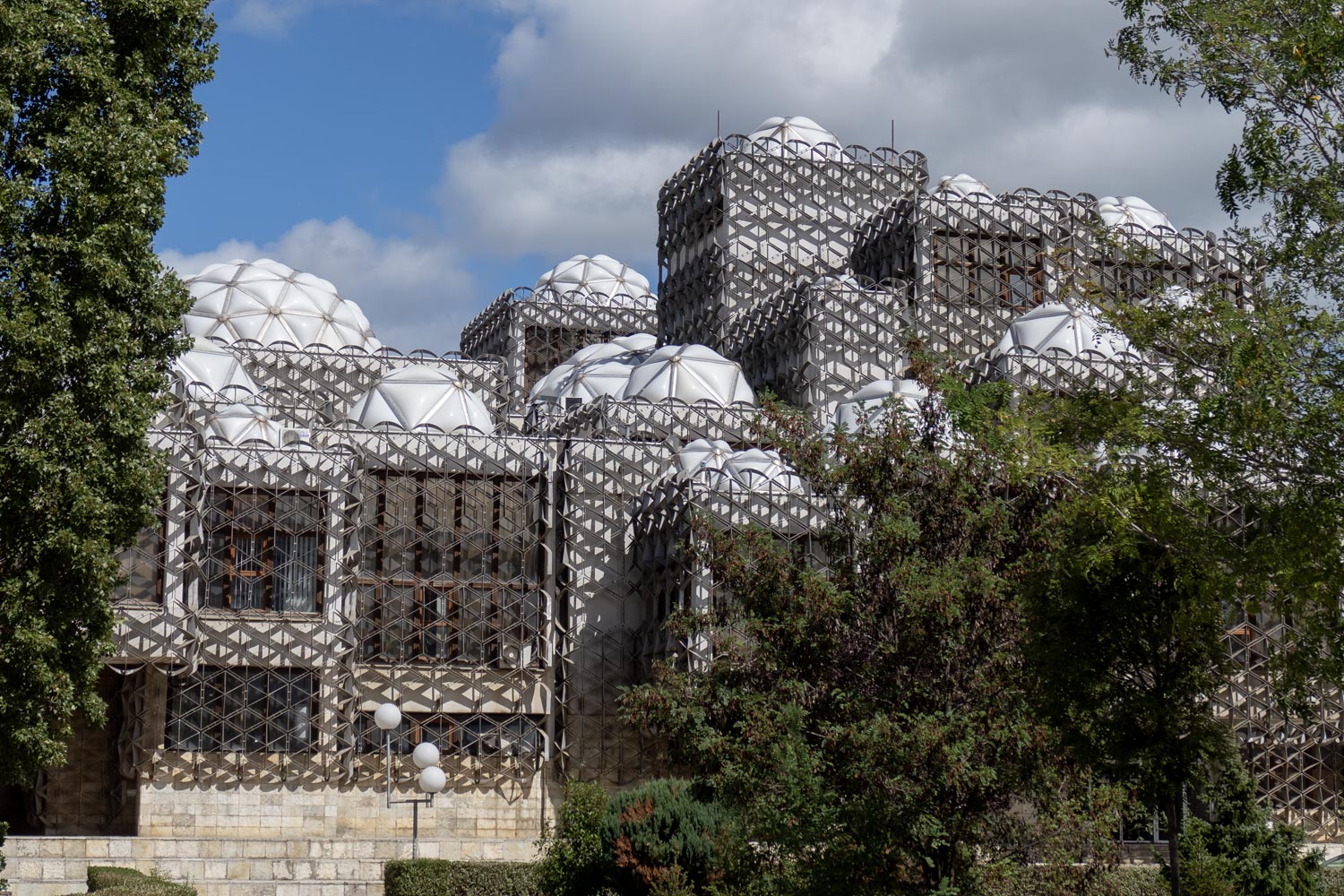

As for the center of Pristina, it is a mix of panel buildings and historical architecture. It’s no longer Europe, but not quite a socialist block either. Here, you can find the National Library, the most famous building in Kosovo.

The library has incredibly interesting architecture. It is an absolutely unique example of Soviet modernism, built in 1982 by Croatian architect Andrija Mutnjaković.

You can enter the library, and the interior is decorated in the finest traditions of Soviet Houses of Culture.

Finally, not far from the library, there is an unfinished Orthodox church. Its construction began in 1992, when Yugoslavia was already falling apart.

By that time, Slobodan Milošević had deprived Kosovo of its autonomy and established direct control from Belgrade. The decision to build the church was made on the territory of the main university campus in Pristina, which was intended to be a place free from religion. Simultaneously with the construction of the church, dissenting professors were being dismissed from the university, and activist students were expelled due to their opposition to Milošević’s policies. All of this caused serious discontent in Kosovo.

Construction was already halted in 1995 due to lack of funds, but they still hoped to open the church in 1999. It was precisely then when the Kosovo War began, and there was no longer any business on the church. Half of the Serbian population left Kosovo, and ethnic riots began.

Nowadays, the church in Pristina is no longer needed by anyone. The authorities cannot even determine who it should rightfully belong to: the Orthodox Church or the university. Perhaps it would be easier to demolish it, especially since the Serbs have their own places in Kosovo.

Gračanica. Serbian enclave in Kosovo

Five kilometers from Pristina is the urban-type settlement of Gračanica. The taxi driver noticeably tenses up when he realizes where he has arrived. Serbian flags hang on lampposts along the road. The welcome sign is also in Serbian.

Memorial leaflets on the poles are no longer highlighted with a colored frame: now an Orthodox cross is drawn.

Gracanica is one of the examples of Serbian enclaves within Kosovo. Another example is the city of Mitrovica in the north. These settlements cannot be separated from the country: they are stuck in it like raisins in a bun. You cannot draw a border around them, but you want to dig them out because these enclaves are vulnerable to ethnic conflicts.

In the center of the settlement stands a monument to some Serbian warrior with a typical inscription: “I love Gracanica.”

Although Kosovo is now a separate state in its own right, something Serbian still remains in the country, and Gracanica serves as a reminder of that.

Kosovo was Serbian until it came under the rule of the Ottoman Empire in 1389 as a result of the Battle of Kosovo. It is analogous to the Battle of Kulikovo for Russia, with the only difference that the Russians won the war against the Mongols, while the Serbs lost to the Turks. Nevertheless, one of the Serbian knights managed to get into the Turkish camp and kill Sultan Murad. The monument is dedicated to him.

Six hundred years later, in 1989, Slobodan Milosevic delivered a speech at the Kosovo Field. In his speech, he used the phrase “Kosovo is the heart of Serbia,” which became a political slogan for Serbian nationalists.

Bravado with this slogan is unlikely to lead to anything good, although there is something in it. The loss of Kosovo for Serbia was indeed a wound in the heart, and it happened twice: once many centuries ago, and another time quite recently.

Gracanica is located on the Kosovo Field, and at its heart stands an old monastery founded in 1321.

It is a UNESCO heritage site. The monastery has survived the Ottoman occupation, World War II, NATO bombings, and ethnic riots.

This means that peace is possible, even between sworn enemies.

Meanwhile, Kosovo remains the poorest region in former Yugoslavia. People are leaving the country in large numbers. According to surveys, 50% of the youth are ready to leave at the first opportunity. The future of the country is very uncertain, and the author can only wish the Kosovars good luck and express gratitude for the warm reception.

Unfortunately, the next visit is not going to be anytime soon. I ended up being the last Russian tourist in these lands for many years. A week after my visit, the authorities of Kosovo announced a ban on entry by Russian passport with Schengen visa.

O tempora, o mores.