Samara

Samara is the best Russian city I have been to.

Samara is some kind of technological paradox. What style is it when shabby skyscrapers encroach on carved houses of the 19th century? Russian cyberpunk?

Samara fundamentally differs from other cities in Russia. I don’t know if it’s the only one, but in Samara there is a pretty clear division between the new and old city.

Or used to be... Usually, such division can be found in cities of the Middle East where medieval mud buildings are surrounded by modern panel houses. Or in Europe, where beautifully restored half-timbered mansions are surrounded by neat business districts.

Samara is taking the third path. It resembles an Asian city where rotten shabby huts are squeezed between cheap high-rise buildings.

The scale here is not as grandiose as in Asia. The huts are not really huts, but rather rich houses from the past. The skyscrapers are not exactly skyscrapers either: they are just high-rises covered in glass. But overall, it’s quite good!

Technological progress has only just begun to engulf Samara. Electric scooters have already appeared, on which local hipsters race over wooden platforms between flower beds, but quadcopters with packages are not yet flying in the air.

Several historical houses have been restored: the facades were repaired, painted, inscriptions were hung on the pre-revolutionary ones; museums were opened inside.

Other ordinary residential houses are left to the conscience of their owners. Rare houses are in good condition. Most of them are doomed for demolition.

Behind the facades of the houses, there are hidden backyards, other houses, various extensions and outbuildings, sheds, and garages. The yard is often shared by several houses. In one of such yards, two families were grilling shish kebabs:

“Good day. Can you tell me how old these houses are?”

“Hello. I don’t know about these ones, but those further down, where we live, were built before the revolution.”

“So, they’re that old?”

“Yes, some merchant used to live in our house. What are you doing here, taking pictures?”

“I came to see Samara. Do you realize that these houses are incredibly cool?”

“Ha, we do. Tourists often come here.”

“So, will they all be demolished?”

“I wish it would happen sooner!”

“Why sooner? Do you want to live in a new building?”

“God, yes! These houses might look pretty to you, tourists, but try going to the bathroom in the middle of a freezing night — you have to run across the garden to the toilet. What a delight! Having an outhouse in the twenty-first century! They might as well raze everything to the ground, it’s impossible to live here!”

“So, you have outdoor toilets?! Well, now I understand. Beauty shouldn't come at the expense of convenience.”

“Exactly. Want beauty? Then install sewage systems, provide amenities, restore these houses. But who needs that? If given a choice, of course, no one would choose such a life. They should relocate us.”

The sadness of urbanists can be understood, but really: in the twenty-first century, no one wants to run to the toilet in the frost. It would be possible to install a sewage system and provide each house with a toilet. But how much money would it take?

And it’s not just about the money. I just don’t know of a project of such scale and complexity. To connect thousands of completely different houses into a single sewage network? To equip a toilet in every house, which may not even have space for it? An unattainable plan that could only be accomplished by the Roman Empire.

Therefore, residents make the only rational choice and choose housing with relocation from two evils.

While not all of the old Samara is yet built up, and there are already several high-rise buildings among the wooden quarters, a traveler has a unique chance to see the old city from a height.

A local resident escorted me to the balcony of one of the panel houses.

“Hello. I came here to see Samara and it looks like this place has a great vantage point for a few shots. Can I go with you?”

“Yes, please, let’s go. What do you want to photograph?”

“Well, these old houses. They’re all up for demolition, aren’t they?”

“They’ll all be torn down soon.”

“That’s a pity. The houses are beautiful.”

“It’s sad. But thank God they’re demolishing them. You know, if you came here in the spring, you wouldn’t be able to breathe.”

“Why’s that?”

“Well, all the toilets are outside. Over the winter so much, excuse my language, shit accumulates that when it gets warmer, we have a sort of a greenhouse, damn it, effect. The whole district is shrouded in mist. But locals know that it’s not mist, it’s steam from the shit. It stinks so badly you can’t sleep.”

“Ah-ha-ha. So, you’re in favor of new buildings?”

“Of course. They should raze all this to the ground.”

Well, they’re demolishing it.

The residents are rejoicing, the urbanists are unhappy, and the market has resolved.

There are real gems among the slums in Samara. Digging through the old ruins, one can find works of art. Someone painted their house in such bright colors that you want to photograph every hook here. It’s like some Spain!

Another corner reminds of Africa. A clothesline is stretched between a brick wall and a birch tree for drying laundry. There’s junk lying around: an old garage, a pile of rust, chairs, and carts.

No need to say. Samara can produce such scenes that one would have to travel to Syria or Argentina for.

And then provide such contrast that it will make your ears ring.

It was Syria — it became Barcelona.

This is the center of Samara. And it is beautiful.

As in any Russian city, there is very little greenery on the central streets. This is the main drawback.

Everything else is in Samara. Architecture:

History:

Coziness:

Modernity:

The city can be studied endlessly. Samara is huge in size, but the main thing is that it is huge in depth. When it seems like all the streets have been walked and all the quarters have been filmed, suddenly an impossible house in the Moorish style is found.

Do you think it’s a museum? A mansion? Ha! It’s actually a skin and venereal disease clinic.

A 19th-century fire bell tower.

The old stock exchange building, now a clinical hospital, with a gastroenterology department.

Whack! The Lutheran Church.

Bang! The Catholic Church.

Boom! Just a regular church.

A mosque. Let’s do without sounds.

An absolutely beautiful Art Nouveau-style Philharmonic Hall that some scoundrel defaced with a disgusting poster.

A theater in the Russian style, built in 1888.

The mansion of merchant Kurlyna in the Art Nouveau style, built in 1903.

The mansion of nobleman Naumov in the Classical style, built in 1905.

The Peasant Bank. It provided loans to peasants in the Russian Empire. Built in 1911 in the Art Nouveau style.

The Postal Service Administration, Art Nouveau style, built in 1910.

The mansion of Klodt. Eclecticism style, built in 1898.

Of course, after the revolution, all these buildings were confiscated by the Bolsheviks. The mansions and estates were converted into various institutions: Klodt’s mansion became a children’s art gallery, and the Peasant Bank was given to a chemical and technological institute.

Under the Bolsheviks, buildings were constructed in a different architectural style and for different purposes. For example, there is the House of the Red Army. Constructivism style, built in 1932. Beneath this building is the so-called “Stalin’s bunker” — a World War II bomb shelter created to protect General Secretary Joseph Dzhugashvili, although he never actually used it.

The Felix Dzerzhinsky House of Culture, Constructivism style, built in 1932.

The House of Industry, Constructivism style, built in 1933.

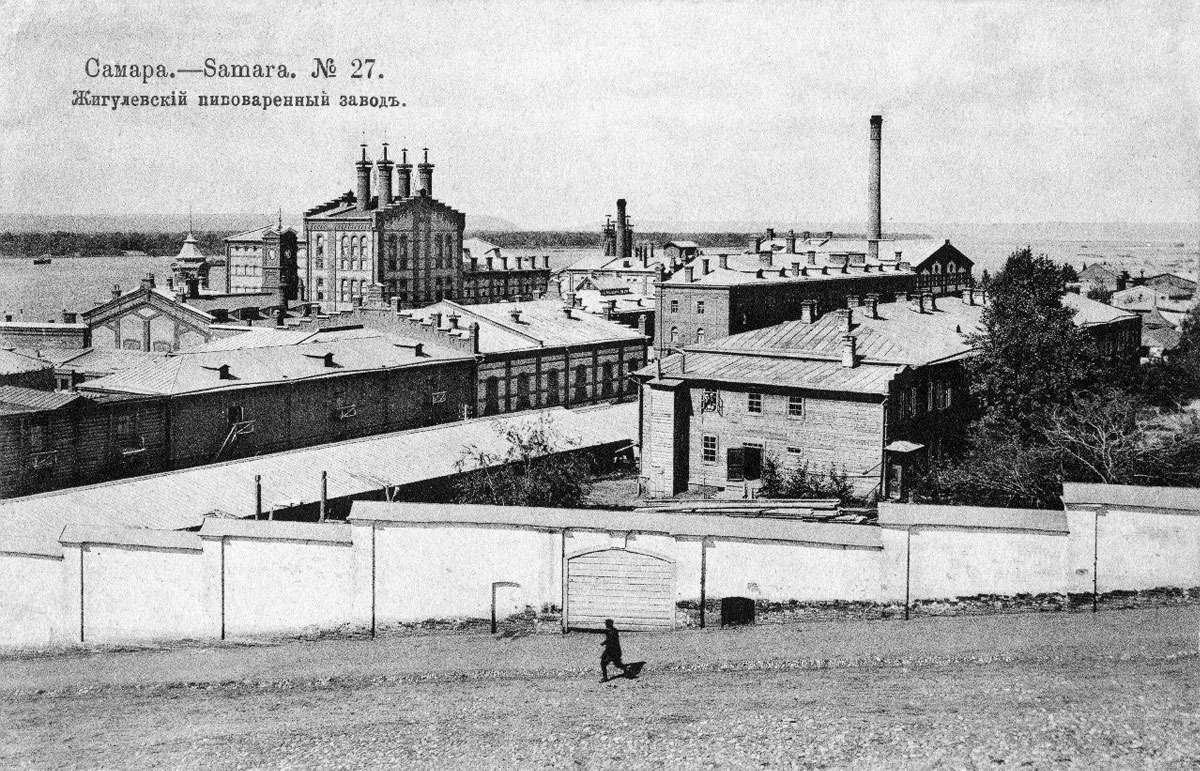

The jewel of the collection is the Zhigulevskaya Brewery.

In general, people in Samara are clamoring for beer. At the store near the brewery, they pour the freshest “Zhigulevskoye”, just brewed. This is one of the largest drug manufacturing plants in the world.

The plant was built in 1881 by the Austrian Alfred von Vacano together with the Samara merchant Petr Subbotin. That is why the plant initially produced “Viennese lager” beer and only in the late USSR did the beer become similar to modern beer.

The plant is located on the bank of the Volga River. Earlier, the view of the plant was a hallmark of Samara.

Now the popes have seriously spoiled it. They built a bell tower right under the windows of a residential building that used to face the river. They stuck some dome on the fence and are building a new church that will completely block the view of the plant.

And here is the bell tower. It stood here for only five years, long before the revolution, and then it was demolished. Recently, the bell tower was rebuilt again. Can you imagine what a gift it is for the residents of the neighboring building? They were looking at the Volga, enjoying the view. Then the popes came and ruined people’s lives.

Nevertheless, Samara is beautiful. The city has absolutely everything for a happy life. The cherry on top is the gorgeous, long beach.

Samara is a resort Russian city on the Volga. Life here is bustling.

A city that anyone interested in Russia should definitely visit.